Comics in Cowboy Land - The Furrow

Photos & story by Laura Read

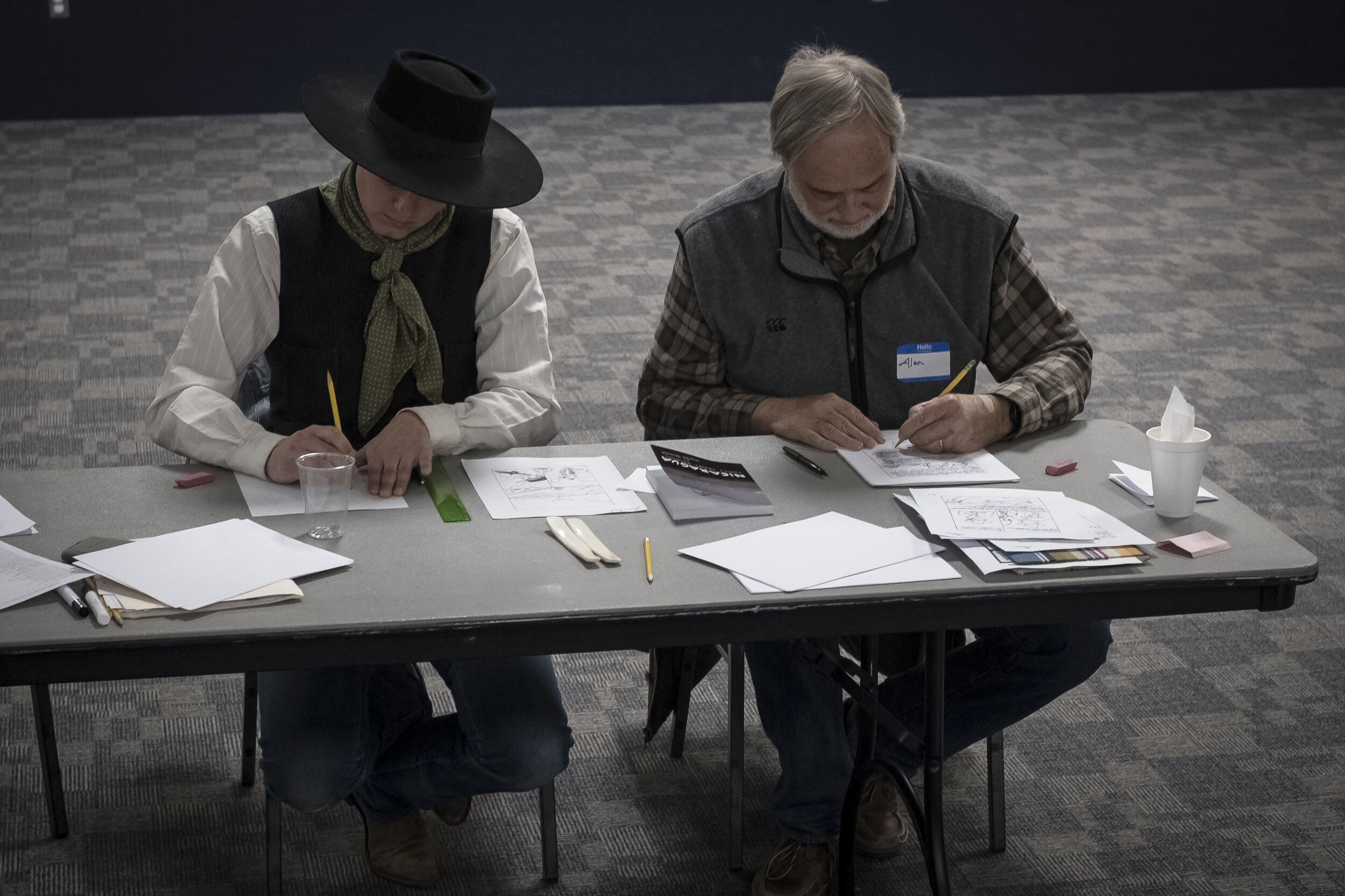

In the first days of the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering in Elko, Nevada last January, graphic novelist Marek Bennett peers excitedly through wire-rimmed spectacles at the adults who’ve clustered in the convention center to learn cowboy comics. The group includes two retired octogenarian ranchers, a couple of practicing ranch owners, and a 20-something buckaroo. There are also city folk from places like Las Vegas, Reno, and Chicago — an investment banker, an insurance broker, a communications specialist, and a member of the media. These are the usual suspects who land in Elko every winter for the week-long celebration of western music, arts, and dance.

The person who is less than usual is Bennett.

A New England native from New Hampshire, the wiry cartoonist wears khakis, converse tennis shoes, and a wool driving cap turned backward — duds that are far from the Gathering’s more common attire of boots, jeans, and cowboy hats. Having a curly beard that sweeps toward his clavicle, he looks like a youngish Abe Lincoln clad in hipster’s clothing.

Bennett and his students represent simultaneous moments in American history that rocked the country into a new age: Folks attending the Gathering admire the Wild West as it was during the decades when 19th century dreamers, wranglers, and shysters spilled out of Midwestern farmlands to settle its unforgiving ranges: Bennett values stories of heartbreak, valor, and change that emerged during the 1860s Civil War.

The two have a parallel of place, too – albeit one that extends across different centuries. Bennett’s hometown of Henniker was settled in 1761, almost 100 years before Elko had a name. Surrounded by lush, forested lands around the Contoocook River, which flows through the Merrimack River into the Atlantic Ocean, Henniker grew up serving farms taking advantage of fertile soil. Bennett now lives on a road named for his grandparents. (They owned a fruit orchard and dairy and his grandfather served for many years as a town selectman.)

Some 2,500 miles to the west, Elko lies in a haunting terrain of dried-up lakebeds and chunky mountains where inland-flowing streams sink blithely into the desert ground. Elko took root a century after Henniker, in 1869, on the banks of the Humboldt River and astraddle the First Transcontinental Railroad. Elko’s first quasi-permanent structures went up just a few years after American leaders declared the Civil War to be over. With nods to the open range, beef cattle and sheep ranchers moved in.

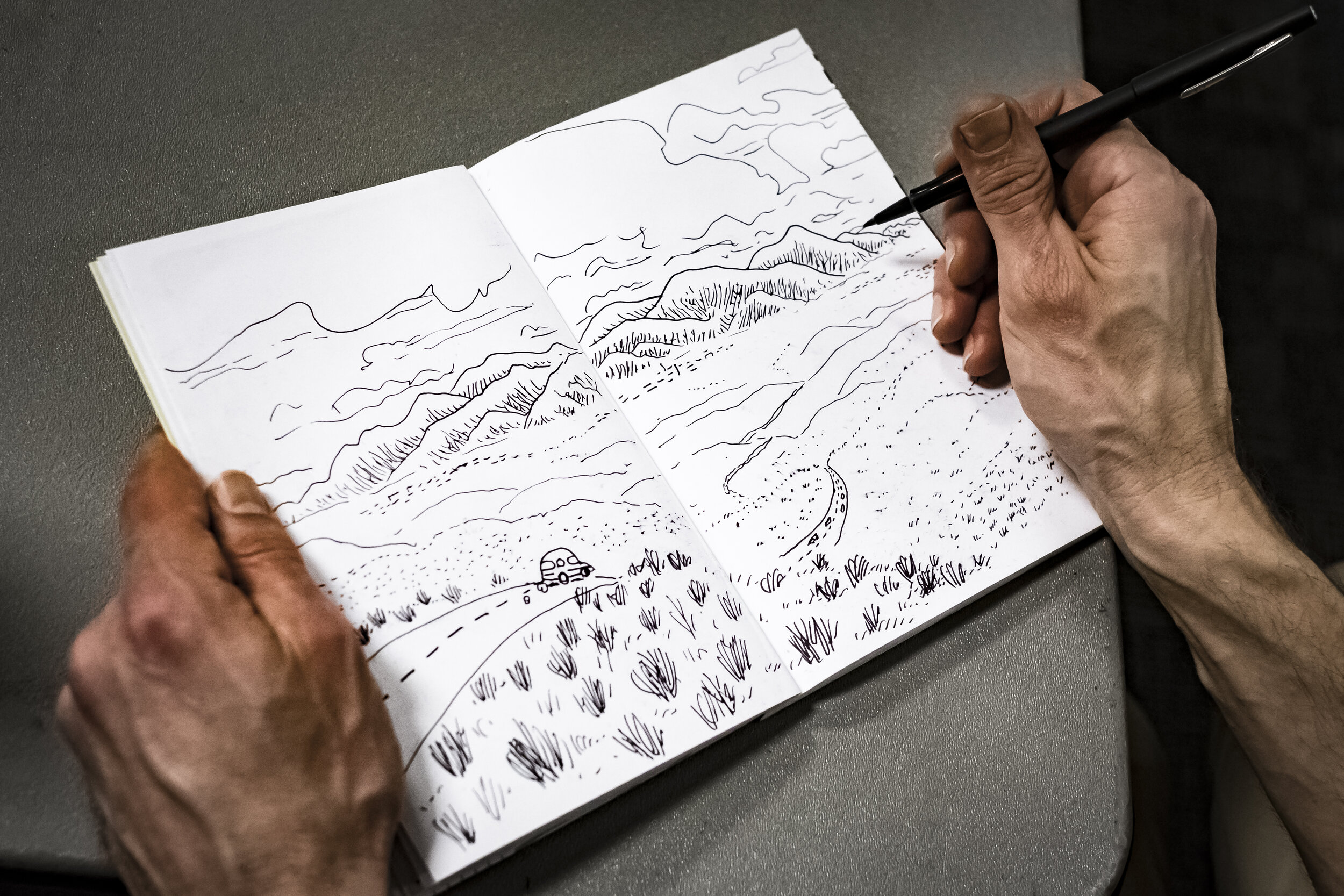

Cartooning History Bennett has many enthusiasms: He plays an 1856-replica banjo in a band called The Hardtacks; he teaches comics workshops around the country; and he educates young artists in schools on the joys of cartooning. But his central focus is making graphic novels about history.

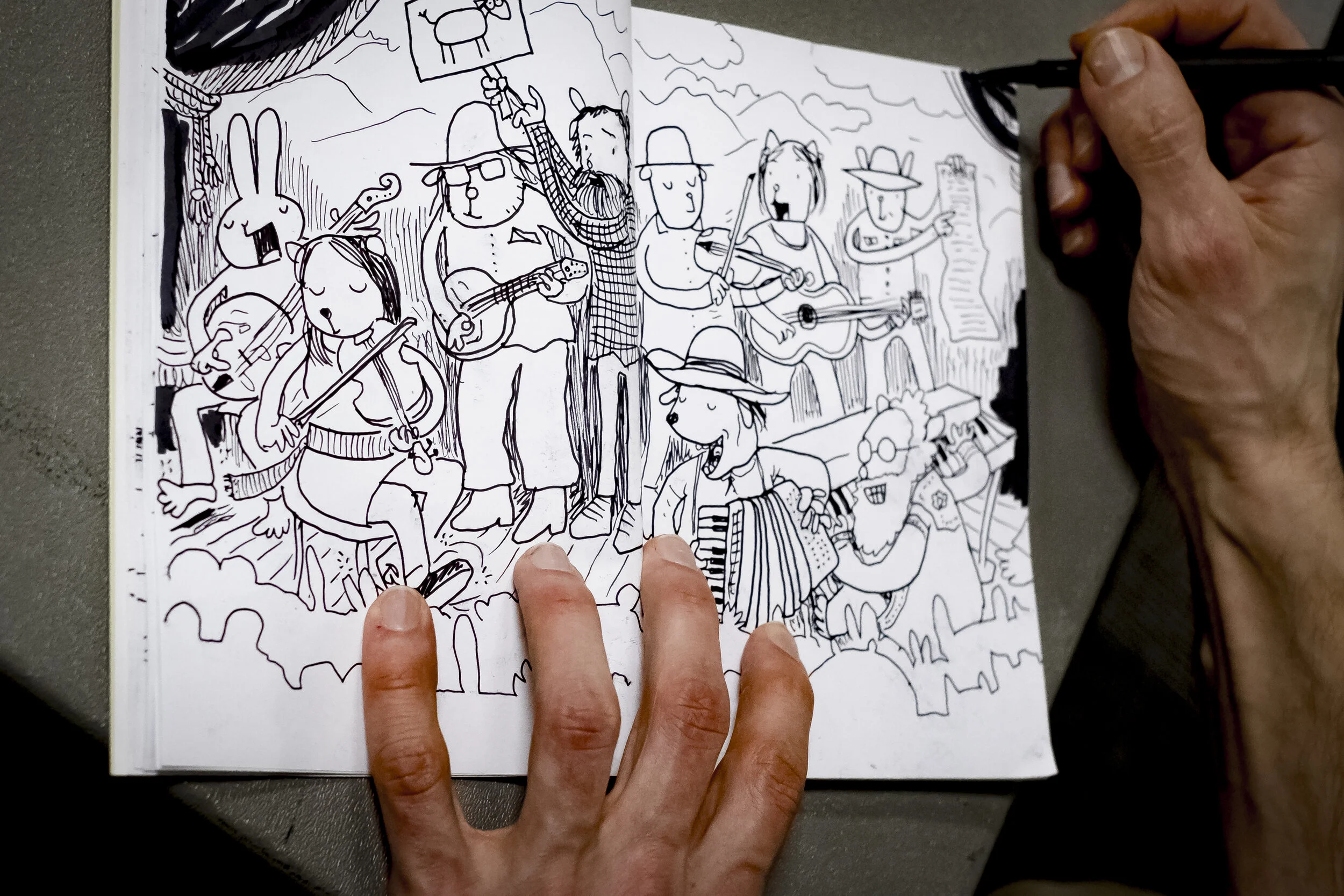

“A lot of graphic novelists are doing really adventurous historical graphic novels right now,” he tells the Elko students at the start of class. His favorites include the 1980s Pulitzer Prize winning “Maus,” in which cartoonist Art Spiegelman interviews his father about the Holocaust, and characters are drawn as mice, cats, and pigs. Another is a 2003 comic strip biography by Chester Brown called “Louis Riel,” about how a 19th century Canadian schizophrenic and rebel leader of the indigenous-French Metis people opposed actions by the government.

Eight years ago, Bennett found his own fantastic piece of the past to retell. In Henniker’s historical archives, he discovered a forgotten 30-page Civil War memoir written by a then-local schoolteacher, Freeman Colby, who described the months he and other members of the 39th Regiment spent building and tearing down camps, repeating endless military drills, choking down “hardtack” flour-and-water biscuits, recovering in sick rooms, and occasionally fighting their countrymen on the battlefield. Bennett knew that if Colby’s stories were brought to life in a graphic novel, they would relate the Civil War in a fresh way.

“I was really curious about Colby's story, and I realized drawing it out panel by panel would help me to understand it better,” Bennett says. “I also felt an urge to help Colby tell his story to a new generation of readers...possibly his first ever generation of readers. I think that diary's been sitting in a box on a shelf for many, many years.”

Admittedly, the Civil War isn’t the first bit of history to flood minds when people think of comics. This bloodiest of all American conflicts, it scarred America’s early territories from Virginia to New Mexico, involving some 3 million fighters and leaving between 620,000 and 850,000 men dead.

“Colby’s story takes place at a cataclysmic meeting point of two worlds,” Bennett says, “an old agrarian world that had existed for centuries, and a new industrial world still forming. It was a fascinating fault line between the Middle Ages and the Modern World. It was that most distant point in history where I could recognize my own world, my own modern perspectives in some of the stories that come down to us. Here was this young school teacher from my town, writing about his experiences along that fault line, sharing his perspectives with us, if we would only take the time to listen — I mean read — I mean draw!”

In 2016, some 340 pages and thousands of cartoon panels later, Bennett published “The Civil War Diary of Freeman Colby.” Its drawn stories are fascinating, funny, and tragic. Enough excitement bubbled around that book that this winter he launched a successful Kickstarter campaign for Volume 2. The book will be available in May.

Cowboys and Comics In the convention center, Bennett warms up his budding artists with a camp humor rhyme called “Boomer Johnson,” written by Henry Herbert Knibbs about a gunslinger who “quits a punchin’ cattle and takes to punchin’ dough.”

“….He built his doughnuts solid, and it sure would curl your hair

To see him plug a doughnut as he tossed it in the air.

He bored the holes plum center every time his pistol spoke,

Till the can was full of doughnuts and the shack was full of smoke….”

When Bennett explains his drawing process, it’s clear his cartoons don’t pop without a hitch onto the page. He first drew Boomer as a human figure in a broad hat and a dark mustache. Then he stepped back. “I got to looking at my characters and thought, ‘Wait a minute; I have made an assumption about cowboys,’” he says. “I’d drawn the types of cowboys I’d seen in movies. Who knows? Statistically, in reality, maybe they were not all white or even all male.’” He redrew the gunslingin’ pastry chef as a figure less threatening, more abstract — a mustachioed swine wearing a vest and cowboy hat. The picture sends the students into giggles, exactly the response that both Bennett — and Knibbs — had in mind.

Is it a Cowboy Poem? The Cowboy Poetry Gathering draws performers from all over the world — from Jiggs, Nevada to Tulare, California, and from Hungary, Italy, Mexico, and Siberia. For years, one question has ricocheted from room to room: “What is cowboy poetry?” Must it have a full story, complete with beginning, middle, and end; contain line breaks, rhythmic beats, and plenty of white space; conjure scenes of cattle thieves, valiant heroes, evil bankers, lurking coyotes, and lassoing vaqueros? Or should it be free from all that?

In 2017, the Elko nonprofit that organizes the event, the Western Folklife Center, hired a new director, Kristin Windbigler, who is kindling a flame under that very discussion.

“In curating this year's Gathering,” she explains, “we wanted to make room for all sorts of stories that show the incredible variety of experiences, opinions, and beliefs among people who make their livings close to the land, and how much those people care about their communities and roles as stewards of the places where we live. I love old western movies as much as anybody, but that is often the limit of what the rest of the world knows about us. The single story of the rugged individualist, for example, is a stereotype of westerners that is a slim view of history and contributes to misunderstandings of how urban folks see the contemporary rural West.”

Reflecting different interests, the Gathering’s program presents all sorts of western skills, from hat making to leather tooling to Basque cooking. Dance classes include Zydeco, swing, and square. Literary functions address songwriting, journalism, and, of course, poetry. Artistic director Meg Glaser says Bennett’s workshop was the first of its kind here. “We thought it would be fun to give our audience and artists and schools the opportunities to try it out, advance their skills, and see where it goes,” she says. “Cartoons and illustrated letters, envelopes, and poems have long been used by the ranching community as forms of entertainment and expression, but using this medium in a longer narrative comic book or graphic novel form is not so common.”

Comic Strip As Bennett finishes his gunslinger segment, his students put pencil to paper, turning their own stories into dots, lines, and shapes. Their pictures have very clear settings – showing the vast grasslands of Montana, the sagebrush hills of Nevada, the salt flats of Bolivia. They have main characters – a stick-figure horseman, a bulging pregnant cow, a wayward traveling son. They have action – tricking the guys who snipped a barbed-wire fence; forgetting to tighten the horse’s saddle before mounting; rescuing an animal from an icy winter pond. And they have text – “Kersplash!”

Bennett chats while they sketch away. “Even though we're drawing different stories in different styles, there's something at the core that we're all doing – some basic visual human communication that connects and informs and empowers all of us,” he says. “You can see it in ancient cave paintings, in images all through human history, and you feel it whenever you just sit down with friends or family and draw, without worrying about ‘Is it good?’ or ‘Is it art?’ None of that judgmental evaluation matters; it's the moment of communication and recognition that makes all the work worth it.”

When a student asks Bennett what goes in to making his characters appear so frisky and full of life, he suggests the students stoke up their own cartooning spirit by emulating the work of their favorite artists. “It will probably change the way you think of yourself, and your story, too,” he says. “Whatever it is, it has to be something that can't be said by anybody else, in any other medium. That's your contribution to comics.”

The Next One After Bennett’s weeklong immersion in the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering’s western lore, is he tempted to explore in his next graphic novel how a buckaroo swashbuckled his way from a hopeless past to a new community? Perhaps tucked in a drawer deep in the Elko historical society archives, a diary of such a tale is craving to be found. Or maybe the long-lost narrative isn’t that of a cowboy, but of a leather worker opening J.M. Capriola Company, Elko’s famous shop of saddles, bits, and spurs; or of a waitress-turned-boarding house owner who slings hot potatoes, soup, and lamb onto tables for famished sheepherders; or a coming of age story about a ranch kid living in the middle of Nevada’s wide-open basin and range.

As Bennett implies — such stories are for an Elko cartoonist to discover.