Rethinking the Walnut Waste Stream - The Furrow

By Laura Read

Five years ago, after finishing school at Georgetown University and then building nonprofit houses in Baltimore, Sean McNamara returned home to his family farm near Davis in California’s northern Central Valley. His parents, Craig and Julie McNamara, had bought a 460-acre property in 1980, and he’d grown up under the canopy of the trees riding nut buggies during harvest time, and munching sour grass in crude tree forts the rest of the year.

While Sierra Orchards was well-run and respected, there were a few methods that the then-26-year-old thought maybe could change. With the property purchase, his family had inherited a process of disposing the walnut hulls generated by their processing plant, or “huller,” into piles that lay disintegrating on their land along Putah Creek.

“My dad and I had a realization that it wasn’t fair to be dumping our hulls right along the edge of the creek.” McNamara says. “It was a way of brushing the problem under the rug. We weren’t proud of it, and we wanted to restore that area.”

Shell parts were already being ground up and used in sandblasting materials. McNamara wondered if the hulls couldn’t be used in compost somehow. Meanwhile, the family also was working on another important goal: improving the quality of its soil.

Trash or Treasure: At Georgetown McNamara, who is the grandson of former U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, had majored in American Studies, a multidisciplinary field that blended his many interests into one stream, interests that included art, history, sociology and politics. An independent thinker, he had intended to go into urban planning, but the Great Recession had thrown him a curveball. Back at Sierra Orchards, looking for new ways to make the orchards more productive and better resistant to disease, McNamara found himself immersed in communities of a different kind — the endless webbed networks of fungi, bacteria, and minute earth-dwellers such as nematodes, arthropods, and protozoa. These are populations that make soil.

“The first thing was learning the magic and complexity of soil, and the differences between ag soil and wild soil, and asking the question how we could manage our ag soils more like wild soils, like soil in the forest,” McNamara says. “Fungi mycelium can perform all of the important jobs in the soil — the decomposition or conversion of organic matter and molecules into plant-available nutrients, the delivery of those nutrients to the roots of the tree, even the delivery of water to trees that are water stressed.”

He needed to set the stage for better fungi development in the soil, and he wanted to do that by reusing something that was already being generated on the farm, maybe by using the crushed limbs, leaves, and trunks left behind after orchard removal for compost. Was there anything else he could use, he wondered. Perhaps the abandoned piles of hulls….

Deep Research: His dad was initially skeptical about using the orchard leftovers, advising that it was important to keep any natural walnut trees threats, such as the parasitic fungi Armillaria, from overwhelming the compost. Additionally, there were questions about whether the hulls were toxic. McNamara sought help from his neighbors and friends to resolve these uncertainties.

“I learned the basics from my community, from the guidance of my friend Max Brotman, and from illuminating books such as ‘Teaming with Microbes’” McNamara says. (The 2010 book from Timber Press is by Jeff Lowenfels and Wayne Lewis.) “We did some due diligence in the form of chemically analyzing the hulls prior to composting, but we never knew how well it could work, and how much we would learn by doing it.”

Useful information came to the foreground as he and Brotman used Google Scholar, a search engine, to scan many different sources of scholarly work including articles, books, abstracts, and theses.

After presenting the solutions to his dad and getting the okay, he was ready. He devised a one-year pilot program, and he’s been refining the process ever since.

Getting started: “When we harvest the walnuts, we shake the trees with a shaker. A bunch of stuff falls down, leaves sticks, nuts, the outer green hull — they all come down,” says McNamara. “We sweep them to the middle. We pick them all up and then bring that whole bundle of stuff to the hulling plant.” The plant sorts the best walnuts and sends the rest out a trash chute. “By this point — this is in October — they’ve oxidized; they’ve turned black,” McNamara says. The trash chute emits thick vegetative matter that is perfect for mixing with the crushed orchard remains, he says.

All the Stages: Assembling the long compost windrows is only the beginning of the process. “Compost requires the right ratios of carbon to nitrogen in the windrow,” he says. “Those are the materials. The process, which we engage in with the microbes, involves heat, water, mixing or aeration, and time. The cure stage involves all these elements, but happens after we have assembled the right ratio, added the right amount of water, and mixed to control temperature, oxygen, and moisture.”

During the hot stage, McNamara says, “a thermophilic heat-loving bacteria colonizes the pile and helps break things down more quickly. Then, it’ll cool down from maybe 150 degrees.” During that period, the bacteria and fungi need time to form relationships, “to recolonize,” he says, “because those are what you want to reintroduce to your soil. You want it to be full of biology. If I’m doing a good job and getting lots of fungal diversity, a tablespoon of compost might contain five miles of mycelia cells linked together. It might have billions and billions of bacteria and millions of species of bacteria.”

Conscious of using as little groundwater as possible in the process, McNamara realized he could recycle the water that resulted as a residue from the walnut shelling process. “It’s been an infrastructure hurdle to hydrate the compost with this sludgy wastewater that is generated half a mile from the windrows. We have to keep everything moving, keep the equipment from plugging. Now we’re hydrating almost completely with already used water, which feels really cool.”

Diversity: “We played with ways to introduce more biology,” he says. “The limitation of this compost is that we’re only harvesting the biology of this area, because we’re using the walnut wood chips and the walnut hulls.” He wanted to bring in even more diversity, and found it in a compost made by a biodynamic winery in nearby Sonoma Valley. “They pull in all kinds of substrates for their compost,” he says, “and it’s super biologically diverse. I take a couple of bags of that and make compost tea with it, and inoculate this compost with the bacteria and mycelium and everything else. That’s fun.”

With water, with organic material, with sunlight, the compost does its thing.

“This is where compost is a dance among nutrients — like carbon and nitrogen — a dance between those two things, plus moisture, temperature and time,” McNamara says. “We want everything to go back to the soil. We want to close the loop of this system. The compost has been a nice way to do that. The compost has been a catalyst for thinking about waste streams. What’s the highest and best use of these waste streams?”

The intensity of work is as satisfying as the problem-solving. “It’s just a high-energy, dynamic process,” he says. “We are harvesting the walnuts, working long days and long weeks, and composting this fresh product at the same time. We balance out how to do that, time- and energy-wise. It’s a constant learning experience.”

And immensely satisfying to know that through asking questions, testing, tapping the community and internet for answers, then addressing problems one by one, a useful retooling can take place. “Something we considered for 40 years to be a waste product turned into being something incredibly valuable to us,” McNamara says. “Now, what else can we look at?”

Thinking Big at Bently Ranch - The Furrow

Photos & story by Laura Read

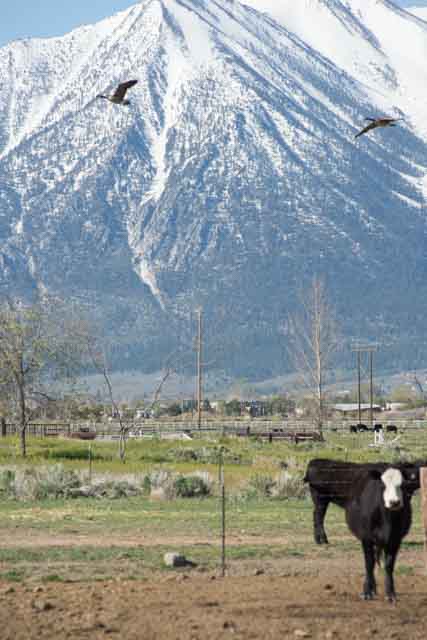

CARSON VALLEY, NEV. IS NAMED for Kit Carson, the 19th century trapper and scout who guided John C. Freemont on his 1840s explorations of the American West. The valley spans 14 miles between the granitic bulk of the Sierra Nevada and the high desert curves of the Pine Nut Range. At its heart is the Carson River, which originates on the slopes of California’s Sonora Peak and – flowing improbably away from the Pacific Ocean – ends in the Nevada desert, where it sinks into the earth.

Today, a new kind of advance guard is at the helm of one of the valley’s largest ranches. Christopher Bently, 48, took over running Bently Ranch in 2012 after his father, the inventor and electrical engineer Donald E. Bently, who was running it as a beef cattle ranch, passed away. The ranch now includes about 65,000 acres located in four western regions: in Carson Valley, near Lovelock, Nev. and near the towns of Bridgeport and Red Bluff, Calif. While Carson Valley has felt the nip of new housing at its edges, much of its center has remained open – quite a bit of it devoted to cattle ranching and wetlands preservation. The younger Bently wants to continue the ranch’s heritage, but he also wants to grow it in a new direction: Next year he’ll open Bently Heritage Estate Distillery inside of restored 1906 mill and creamery buildings in the town of Minden, population 3,000. The distillery will produce gins, vodkas, whiskeys, and other specialty spirits. Most of the ingredients will be grown right on the ranch.

“This has been a hard-working ranch for a lot of years,” Christopher Bently says. “It is my goal to protect as much open space and as many beautiful historic properties as possible so that we may retain our environment and culture for future generations.”

Heritage: Bently’s plan is rooted in the legacy of his father. In 1960, Don Bently, then a 36-year-old electrical engineer from San Francisco, bought some acreage in one of the valley’s oldest ranches. Established by the German immigrant H.F. Dangberg in 1857, the Dangberg Ranch filled a portion of the northern end of the scenic valley corridor along U.S. Route 395 south of Reno and Carson City. Comfortable thinking outside of the box (one of his alma maters, the University of Iowa, called him a pioneer and a visionary), Don Bently saw in the section that he bought, a way to combine the two driving forces of his life: his ground-breaking engineering work, and his respect for agricultural landscapes.

In the beginning, he built a laboratory and headquarters for the research, development, and production of his inventions. Eventually the Bently Nevada Corporation became a $200-million-per-year manufacturer of his ground-breaking electronic systems used to monitor the mechanical conditions of machinery.

It wasn’t until 30 years later that Don Bently turned more attention to agriculture. In 1997, after slowly acquiring a total 35,000 acres of the Dangberg Ranch, he established Bently Ranch to raise beef cattle and alfalfa. As he reduced his ranch’s energy footprint and restored its natural wetland systems, the ranch was lauded by many observers as an example of sustainability.

Fermentation: When Don Bently died, Christopher was head of the San Francisco-based Bently Enterprises, known for its LEED-certified (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) renovations of significant structures like San Francisco’s old Federal Reserve Building. The younger Bently had grown up in San Francisco with his mother after his parents divorced. He loved the tradition and purpose of the ranch, and he loved Carson Valley.

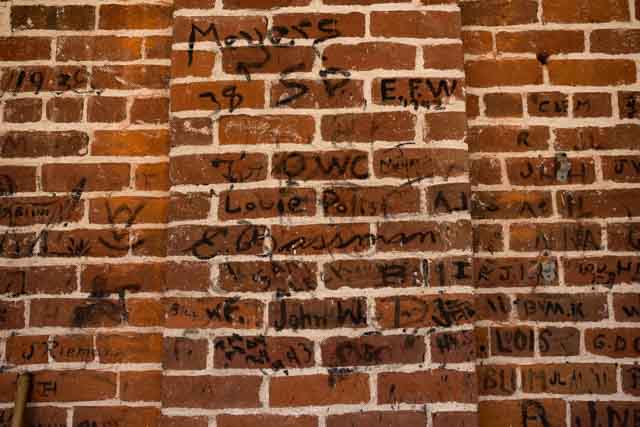

Having as a kid prowled the old empty ranch buildings on his family’s property, Bently is fond of their contributions to the area’s historic character. In the town center, during the first years of the 20th century, the Dangbergs had developed the Minden Flour Milling Company and the neighboring Minden Creamery; both are now listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Bently had a strong desire to build a distillery, and saw opportunity in a boom of independent distilleries taking off across the world.

He and his team proposed restoring the old brick flour mill and creamery, installing state-of-the-art equipment, and opening Bently Heritage Estate Distillery.

Changes started in the ground. General Manager Matt McKinney replaced some alfalfa fields with four kinds of barley and seven types of grain, including rye, corn, triticale, hulless oats, and spelt. He set about identifying heritage grains good for alcoholic brews and spirits.

Because breweries were multiplying in regions nearby, ranch managers began looking at growing hops. (There are 623 small breweries in California and 37 in Nevada, according to the Brewers Association — at least 25 of the Nevada facilities sit between the cities of Reno/Sparks and Carson Valley.) A total 1,500 hops of different varieties were planted — including chinook, centennial, and cascade. “They take 30 percent less water than legumes and alfalfa,” says Woody Worthington, ranch operations manager. This year, the ranch finished building a 20,000-square-foot malting and grain processing facility that includes 200-, 400- and 2,500-ton silos.

The additions fit Christopher Bently’s commitment to sensitive animal husbandry practices. “It is imperative that we conserve natural resources,” he says, “and that we have complete control over how the animals are raised and brought to the consumer, while ensuring that our cattle don't have a negative impact on the surrounding countryside.”

Herds are moved to fresh pastures as needed in order to maintain grass health, and cattle are allowed to grow at a natural rate rather than being fed to speed weight gain, Bently says. The ranch uses solar energy when possible, and recycles organic materials into compost, according to Worthington.

Field to Flask: As for the mill and creamery compound, which occupies a couple of Minden blocks, renovations have been dramatic. In 2014, with the help of the Nevada State Historic Preservation office and an industrial archeologist, about two dozen pieces of machinery were cataloged and photographed. Floor plans were made showing the locations of the old machinery inside the building, according to Bently. Some of the stored machinery will be on display once the finished building is open to the public next year.

The mill renovation included installing floors and catwalks inside the three-story grain silos for access to a new mash tun (which converts starches in crushed grains into sugars for fermentation), as well as fermentation tanks and handmade stills from Scotland. These will produce a Bently Heritage single malt whiskey. The creamery building will hold German-made stills to produce Bently Heritage vodkas and gins. All ingredients will be ranch grown, Worthington says.

Thinking forward: What people in the tasting room may not realize is that, even as Bently is making his ideas a reality, he’s inspiring the next generation of entrepreneurs. As the estate distillery readies to open, research and development percolates inside of a smaller “incubator” facility nearby where food chemists, distillers, and other creative problem solvers are concocting new alcoholic spirits formulas. They often collect flavor ingredients by prowling the high desert, plucking shrubs, flowers, and grasses they hope will ultimate taste divine.

“I’m a big believer of letting people do their jobs,” Bently says. “We have an incredibly talented pool of people who are all part of this. It’s fun to see people excel. They have great ideas.”

Wizard of Hardscape: Mosaic Landscape Artist Carol Braham

by Laura Read

Homestead Magazine

In 1992 when Carol Braham and her husband, Bob, moved north from southern California to a stately neighborhood in Los Gatos, California, they bought the ugly duckling on the block — a 1970s spec house that would need a dramatic makeover. Braham was a schoolteacher by trade, but also in her previous hometown she’d been enrolled in a regional occupation program to learn stone mosaic and masonry techniques. In Los Gatos, she decided to be the general contractor on the remodel, and would do as much of the physical work herself as she could. It would be a perfect chance to employ all of the skills she’d learned.

Doing the construction around the needs of her growing family (her husband is a tech-industry marketing executive, and they had two young children at the time), she and her crew patiently, carefully built the house and yard section by section. As it took 12 years to complete, the project essentially matured along with the family — and ushered Braham into a new career creating stone and pebble hardscapes for her new business, Artistic Creations.

The move was a fit for her personality. “I just loved the work,” she says. “You build it, and it stays. It’s not like when you cook something and eat it, and then it’s all gone. You can see what you’ve done and you can create something that is beautiful and lasting.”

Slow Remodel Separated from the Pacific Ocean by the Santa Cruz Mountains, Los Gatos has a moderate climate that once supported orchards of grapes, prunes, and apricots, and now hosts about 30,000 established families and Silicon Valley entrepreneurs. When Braham bought the property, she was pregnant with their second child. The family moved into the home and did some basic remodeling. When the projects expanded and they could no longer live among the work, they moved into a neighbor’s “little garage” across the street.

For the next year and a half, Braham and her crew tore the original house down to the joists. “The whole thing was gutted, and we added a second story,” Braham says. “We got it to the point of getting a certificate of occupancy, and then we moved back in. I tiled the kitchen and bathroom, and made the fireplace surround and built the chimney.” After the kitchen cabinets and appliances were installed, the work began in earnest on the exterior, which Braham and a carpenter covered with shingles. “I was the corner master,” she said. “You contour each corner piece and make it fit right. You scribe it, cut it, plane it and pin nail it down.”

It took months, but by 2002, the house was finished. However, there was yet another big plan to complete: The yard. Braham had lots of ideas for it, and during the next five years, as each section came together, the yard became a catalogue of ideas. “It’s been my laboratory,” she says.

Stone connectors The landscaping was conceived as a series of “rooms” made for contrasting uses and moods. She used hardscape patterns to both differentiate and coordinate the spaces.

Since the house is on a corner lot, there are two front yards for the many dog walkers and pedestrians to admire, one leading to the front entry of the house, and another flanking the driveway and garage. After you enter a white picket gate to the front, you can either approach the house, or veer off on a path of river rock and flagstone. The “wandering path,” as she calls it, passes a wooden swing that hangs from the branches of an oak tree. The 100-year-old coastal live oak is one of two historical oaks on the property that are protected by a city tree ordinance. “We bought the property because of the two oak trees, and we’ve considered them in everything we’ve done,” Braham says.

The wandering path concludes at an arched gateway leading to the backyard, which encloses an entertainment area, a “parlor” arrangement of teakwood chairs for chats with friends, and a pretty fishpond cornered off against an inspiring mosaic wall.

If there’s a backyard figurehead, it is the property’s second large oak, which fades into the clouds on misty cool mornings. Oaks require a lot of water, Braham says. The landscaping around the tree was designed to encourage the percolation of to the roots through the mulch, stone joints, and sand that beds the flagstone and brick pavers. “The mini-mulch is great because as organic matter it breaks down into the soil,” Braham says. “And it looks nice.” The mulch also functions as a bedding for devotional medals that Braham’s mother-in-law secretly plants under the top layer for good luck. Occasionally the medals surface as shiny forget-me-nots to be discovered by whoever passes by.

Around the side of the house, the yard narrows. Its focal piece is a Tree of Life mosaic in a wall of Connecticut bluestone. Stone-cut leaves display thoughtful words. The wall is a prime example of the permanence that Braham likes so much. “It is a block wall reinforced with rebar on a foundation,” she says. “It’s not going anywhere! I cut river-washed flagstone and used those pieces as a veneer for the design.”

A fishpond burbles at the wall’s base, and a teakwood bench provides a chance to sit and relax a while. “It’s really lovely when the sun is right in the late afternoon,” Braham says.

The spot next to the Tree of Life fishpond has an entirely different mood. Braham removed the garage that stood there originally, and enclosed the space as a desperately needed storage yard. She crowned one wall with a pebble sun motif, and then splashed the ground with a delirious, and time-consuming, composition of sunbursts and ribbons.

A gate nearby transitions to the driveway side of the house, where Braham and the landscape designer who helped her, Rhadiante Van de Voorde of Elemental Design Group, created an angular knot garden counterbalanced by an espaliered apple tree, trained onto a matrix lattice along the fence. The tree is both decorative and practical. “I wanted to see that structure on the fence as a design element, but also was excited about being able to grow fruit in a small space,” Braham says. “I am definitely limited by both space and sun, but my little granny smith apple tree still does well.”

The third element in this section is a bench mounted on a stone footing embedded with a quote from Sir Walter Scott, which reads, “Nothing is more the child of art than a garden.”

“I like planting surprises that give you a little something to think about,” Braham explains. It’s an impulse she apparently shares with her mother-in-law, the planter of devotion medals.

In a nod to ancient farmers like those in Ireland, who piled field rock without mortar into walls that have endured for centuries, Braham composed long-standing dry stack walls to frame flowerbeds along the street.

Since started construction, Braham has waved to many a dog walker pausing to watch her work. “Now they say, “Hey, I’ve been watching you for years!’” she says. “They call me the crazy lady who works on her house.”

Anyone lucky enough to explore the yard will know that Braham is not crazy, but rather a wizard of design blessed with a sure sensitivity to pebbles and stone.

Art of Stone: The Souls of Bill Castellon's Rocks

by Laura Read

Homestead Magazine

Many people think of gardens as showcases for flowers, but to garden builder Bill Castellon, they are all about rocks. For eight years he worked with master landscape designer Mas Imazumi, honing the Japanese approach to placing rocks in poetic compositions. Now he is one of the few in northern California who is especially gifted at the craft.

Castellon’s garden interests started after high school when he worked at greenhouses in rural Pennsylvania. In 1975 he moved to San Francisco, where he became intrigued with bonsai, the Japanese art of growing miniature trees in small containers. One day in a bonsai class taught by Imazumi, he showed his teacher a photo of a rock composition he’d recently completed for clients. “Mas looked at it and said, ‘Next time get me to help you!’” Castellon recalls. “I did, and we built 10 gardens together before he passed away.”

To be a rock specialist in the Japanese tradition is to be trained in creating gardens that often suggest water, but in fact contain no water. These are called dry landscapes. Two of Castellon’s favorite projects display two common types: the karesansui, or viewing garden, and the stroll garden.

In Lafayette, Lisa and Andy Mayeda installed a karesansui on top of a reclaimed swimming pool. Landscape architect Sue Oda drew the overall plan, which splits the meditation garden into two asymmetrical lobes hinged by a central peninsula, like the two humps of a heart. The Mayedas commissioned Castellon to give the rocks their alluring placements.

Castellon’s challenge was to find rocks of just the right scale and shape, and to arrange them for soothing harmony and balance.

“You want all the rocks to be of different sizes or to appear to be of different sizes,” Castellon says. “They vary in height and spacing. It’s a challenge to make the garden look not contrived.”

He’s an expert at recognizing a dynamic energy created when objects are placed in relationship to one another. “The dynamic tension is what we hope for,” he says. “In the old dry gardens in Japan, there’s a play of energy between the rocks. The vertical lines create tension, the horizontal lines create serenity and stability, and the diagonal lines create motion.”

The rocks come from the northern Central Valley, where over many years they’ve grown blooms of moss and lichen on their faces. Once settled in the garden, the rocks may suggest mountain landscapes. “Or they can represent family units,” Castellon says. “The mom and dad are the bigger rocks, and the younger children are the rocks close by. The elder child often has left home and is alone off by itself.”

Sometimes it’s clear exactly where the rock belongs, and at what angle, Castellon says. Other times, the placement can be quite a challenge. “It’s an emotional thing,” he says. “If it’s not right, I’m not happy.”

Lisa Mayeda says the garden is exactly what she wanted: a place for reflection and enjoyment. “In the evening, the lantern light comes on and the rocks seem to glow,” she says.

“You’re always playing with people’s senses when you’re doing a Japanese garden,” Castellon says. “It’s a lot of fun.”

A few miles away in Olinda, Stu and Jane Bowyer’s stroll garden encourages the viewer to go slow and wander. Castellon’s dry landscape complements a previously built Japanese-style waterfall. His concept begins at the Bowyer’s driveway, where a craggy Japanese black pine tree welcomes visitors. Trees like this are grown in pots for as many as 50 years, and their limbs are pruned by experts to form attractive patterns. At the garden gate there’s a vignette of a black pine and two rocks set to appear as if they were once joined and now have cracked apart.

A path rounds a corner to where the garden unfolds with magical serenity. There is no water in this half of the garden, and yet there’s a mysterious suggestion of water, achieved partly by contrasting scales, colors and textures. Small pebbles cause a flat area to resemble a lake that’s reflecting gray clouds. Stepping stones beckon the viewer to meander across it. At one point they tuck into a “bay” where a person can pause by a dry streambed.

Across the lake, the path diverges. One route climbs to a waterfall overlook; the other circles to the waterfall’s base. The result is a slow immersion in a setting of simple, natural beauty that speaks to the elegance and wisdom of age and time.

Sabastopol's Junk Artist Patrick Amiot

by Laura Read

Homestead Magazine

Turn the corner three blocks from Sebastopol, California’s main street, and enter Florence Avenue, a place where residents and visitors love to stroll — not to see any flowering landscapes, but for an exhibit of giant recycled art sculptures that colonize the lawns. Some of the towering works — the ambulance drivers, truck drivers, firemen, and farmers — represent the kinds of people who make American towns do what they do. Others are creatures of fiction borrowed from fairytales and comics —the White Rabbit, a mermaid, Batman, the Three Little Pigs. Together these characters have transformed the once sleepy neighborhood into a parade of America’s quirks and charms.

The French-Canadian-turned-Sebastopol-residents Patrick Amiot and his wife, Brigitte Laurent are the artworks creators. The two have lived on Florence Avenue for almost 20 years. The situation on their block today is quite different from what they found when they arrived from Montreal in 1997, when, Amiot’s wry sense of humor, and the complicated ceramic artworks he made at the time, set him apart from his neighbors. Then, he felt like a stranger. But after a world tragedy collided with his fondness for creative risk, he became the neighborhood’s main theme.

“This is a really important part of my life,” he says as he sips coffee on the shady front porch of his 1905 Queen Anne. “I owe a lot to these neighbors for their support.” Two ladies on the sidewalk gawk at a giant Godzilla that is frozen in mid-destruction in his front yard. In one hand the lizard crushes a windmill plucked from a country farm. In another, he hoists a car and its driver into the air. The terrified driver’s hair stands straight up on end.

Amiot and Laurent’s relationship with Florence Avenue began in May, 2001 when, at a low point in his ceramics career, Amiot made a decision to shift gears. He scrounged up an old row boat and a used wheel barrow, put the parts together, and made a junk art statue of a fisherman in a boat. Friends and neighbors loved it, and that encouraged him to try again. For his second work he went big, choosing one of his adopted country’s favorite icons: The Statue of Liberty. He never imagined his originality and timing would clash so significantly.

“I’m Canadian and the Statue of Liberty represents America for me,” Amiot recalls solemnly. “I put it up on September 10, 2001, and it was just another day. But the next day was September 11. The World Trade Centers collapsed, and there was a lot of emotion and confusion.” As the public reeled in shock, his two daughters worried the unconventional Liberty might get misinterpreted among the waves of 9/11 grief.

“I completely agreed with them that it was awkward,” he says. “I told them, ‘Tomorrow I’ll take it down.’ But the next day I woke up and there were a bunch of flowers and letters at the statue. I didn’t know what to do. Should I take it down or leave it there? So I wrote on it ‘In memory of all the innocent people who died September 11.’”

With his intentions clearly stated, his Lady became a shrine for the lost loved ones of 9/11. “That was the beginning of my relationship with my street and the neighbors,” Amiot says. “We started talking, and then I wasn’t such a stranger.”

Awhile later, he constructed a giant fireman for a 9/11 fund-raising auction. Not a soul bid on the piece, but after the event a neighbor asked if he could display it in his yard. “So I had a big fireman across the street with a big heart that glowed,” Amiot says. “The next thing I knew, there were 10 of them in the neighborhood, and it became an attraction.”

One commission begat another, and now more than 200 of Amiot’s characters are providing vibrant notes all over Sebastopol and its vicinity. Sebastopol is in Sonoma County, about an hour’s drive north of San Francisco. People travel the area to shop and taste the artisanal products and wines made from the abundant local fruit. They also come to see Amiot’s works, which are scattered through nearby towns such as Graton and Occidental, and stand at the edge of farmlands and businesses outside of Sebastopol. A free sculpture tour web app is available for download at patrickamiot.com.

Florence Avenue is rarely without admirers pausing to get an eyeful of the grand personalities. Sometimes a customer buys one and takes it away. When Amiot replaces it, the street’s narrative changes.

The house where Amiot and Laurent live is Queen Anne on the outside, but on the inside is an explosion of vitality. His junk art characters crowd up against artworks made by friends and the heartfelt assemblages he’s to mark his wedding anniversaries. Some of the sculptures originate in the backyard, but most are built a bicycle ride across town on a piece of property squashed between the Gravenstein Highway and a pasture smelling of sunbaked wheat.

Every morning contains endless possibilities. When Amiot arrives, he enters a junkyard wonderland. There are piles everywhere: bedframes, jerry cans, and sinks; toy cars, rusty trumpets, and signs. There are collections of clock faces, heaps of engine blocks, and forests of ironing boards; there are mazes of tractor grills, mufflers, and random steel pipes. It is a kingdom of metal, an empire of instruments, a Valhalla of half-made beings, the rust-veined, metal-faced equivalents of brainstorms.

Crammed in one corner are sections of an animated carousel commissioned by a Canadian developer for the city of Markham in Ontario, Canada. It’s the biggest project Amiot and Laurent have ever had, and they’re almost finished. There are no precious horses in this solar powered carousel. When it’s installed, kids will ride on fantastic figures that are all things Canada, from a moose to a Canadian Mountie, to a leather hiking boot.

Today’s project is an eight-foot-tall dog. As morning sunlight steams the chill out of the dry September fields behind the fence, Amiot uses a welding torch to fire a line of pinprick holes into the side of a 50-gallon drum. The holes make it possible to flex the metal into a bow that serves as the dog’s head. Amiot frees an rusted steel jerry can from a pile (“I have a nose pile and a finger pile”) and attaches it to the face. “I’m into big noses,” he says. “The face turns on the nose.” Grinning behind him is a gee-whiz worker in yellow. The only character Amiot didn’t make in the yard is a toy goblin perched on a shelf; he’s the watchman.

At 10 a.m. it’s time coffee time. The break room is an enclosed high-ceilinged workshop, bright with light, where Laurent is in splattered overalls painting a six-foot metal farmer who’s pushing a wheelbarrow. While Amiot assembles the metal bones of his pieces, Laurent paints the details that bring them to life. The piece is commissioned by the tea company Traditional Medicinals to honor one of its workers. Propped up at the figure’s base is a photo of the man being recognized, a helpful reminder of details of his face and clothes. Laurent swabs a brush into her paint pot and dabs a swath of mustard-yellow onto the green base, making a filigree of sunlit grass. Nearby, three metal farmer-pigs push their own wheelbarrows across lawns painted on vintage metal boxes. “I have wheelbarrows on my mind,” Amiot says, shaking his head.

As espresso circulates, Amiot rounds the conversation back to Florence Avenue, a place that is more personal to him than many neighborhoods are to their occupants. He says he would never have come this far if it hadn’t been for the neighbors there. “I owe a lot to these people. We live in an age where people fight over six inches of fence or the color of a door, and here we’re able to have 25 neighbors agree that having art in your yard is cool.”

He takes another sip of the steaming black drink. “It’s the opposite of a gated community. It lets people in.”

Play Ground: Karla Stahlman's Whimsical Garden

by Laura Read

Homestead Magazine

In 1998, when Liisa Primack first viewed a residential lot for sale at the foot of California’s San Gabriel Mountains, in a space where some people might have seen only a mess of scrub and dirt, she envisioned the garden of her dreams.

The 1.25-acre property existed in one of the nation’s busiest places, Los Angeles County, on the edge of the tree-shaded town of Claremont. To the south, a mix of neighborhoods, shopping centers and college campuses sprawls toward the dense population of Los Angeles. A few miles to the north, the energy of suburbia releases into the San Gabriel’s wooded slopes, where nature offers an escape for hikers, skiers and cyclists, and the landscape shelters the usual array of Southern California animal and birdlife —mountain lions, coyotes, bobcats and the like.

Primack and her husband, Andy, who is in the business of manufacturing aluminum alloy, had three children, one in grade school, one in middle school, and one in high school. The kids needed more play space and Primack needed a place to entertain friends and to garden. The property was perfect. “It was a blank slate,” Primack says. “And it was just the right time in life for us.”

Primack’s love of gardening runs deep. “I must have been 5 when I grew my first flowers,” she says. “They were Zinnias. I would come home every day from school to see how much they had grown. I watered them by hand.”

After the purchase, the Primacks got to work building a house and landscaping the yard. First came the hardscape — the pool, the patios and a sport court where they could play paddle tennis, volleyball and basketball. They installed grass for the kids and planted a vegetable patch and a bed of roses, but put Primack’s flower garden dream on hold.

Time passed, and it was 10 years before Primack was ready to create the backyard she wanted. She knew she couldn’t realize all of her ideas alone. One day after talking with a flooring contractor she and Andy had hired, she discovered that help was just around the corner.

In 2010, the landscape designer Karla Stahlman was launching a second career. After raising a family and managing her husband’s flooring business for 16 years, she studied garden design and then worked for a landscape architect. Now she was going solo.

It was a lucky match — a homeowner with a kaleidoscope imagination, and a designer able to coalesce many ideas into a harmonious composition. “Karla translated my vision into a workable project,” Primack says. “Others want you to do it their way. She was so willing to work with someone who wanted to be part of the process.”

Stahlman was equally thrilled. “This is a family who really celebrates life,” she says.

Hacienda style, the Primacks’ U-shaped one-story home hugs the ground. From the family room, French doors lure visitors into a formal courtyard framed by the house’s two wings. At the far end of it, a whimsical arch of ceramic shapes, made by the artist Leslie Codina, marks the shift from the rectilinear environment defined by the home to the curvilinear garden defined by Primack’s imagination.

Beyond the arch is where expectations end, for nothing about the Primack garden is commonplace.

The backyard is a symphony of visual dissonance and resolution, every surface a play of color and light, every shape either a companion or foil to the one next to it. The pool centers the yard. The rest of the design pivots on several features, or “destinations,” as Stahlman calls them: a bocce court, a duo of palm trees bursting skyward, a chunky guest room cabana framing the backside of the pool, the vegetable patch and the sport court. A puzzle of winding paths and flower beds connects the parts.

A recent tour with Primack started with the most current work-in-progress — the rose garden. Primack planted the garden in a grid pattern years ago when she laid down the sod. She didn’t pull out the roses in the new revision, but instead introduced a winding path to soften the grid.

Stahlman’s influence made all the difference here. The path’s scale is important, for instance. “It is an intimate garden path, a one-person path,” Stahlman says. “The width of it says ‘meander here alone.’” The surface of the path was also an opportunity. Primack scattered marbles there, and their sparkles tempt people to lean close and inspect the small ribbed globes they probably didn’t notice while standing.

Behind the rose garden, in the back of the yard is the fenced-in vegetable patch. Instead of painting its fence a traditional white, Primack made an eye-catching rainbow by coating each picket a different pastel hue. The rainbow palette continues inside the veggie patch in a wall mural painted by Shannon Olsen, a young woman whom Primack hired after getting to know her at the Los Angeles County Fair. A chicken-shaped mailbox mounted on the fence serves as a storage place for tools.

Beside the food garden is a chicken coop. A wall of fruiting passion vines keeps the busy birds screened off from the rest of the yard. Primack and Stahlman took inspiration from how traditional Mexican haciendas have gardens that produce everything a family needs for living. The veggie garden and chickens are part of that. You can also cook and eat in the yard. “In the summer I often unload groceries into the backyard refrigerator,” Primack says. The roofed cabana patio covers a dining table and an outdoor kitchen. More formal dining will someday take place in the bocce court after Primack installs some decorative lights there.

Despite all of the garden’s spaces for grown-up activity, its overwhelming quality is as a playground, teasing out the child in everyone. “This garden fills your soul in so many ways,” Stahlman says.

Who wouldn’t want to be in a yard that makes you feel like a kid? One way Stahlman and Primack accomplished the effect is by incorporating compositions of decorative tile Primack collected in Mexico. Primack asked a tile company to custom paint pieces to match the bocce court bench and other features.

Another is by the juxtaposition of big and small scale — “Alice in Wonderland” style. An overlarge chair, a gigantic folk donkey sculpture, and giant reflective spheres pop out beside arrangements of smaller scale plants. “An oversized chair makes you feel young,” Stahlman says.

The garden also encourages contemplation. One out-of-the-way corner contains a fountain and a giant mermaid mosaic inspired by the luscious figure on the Carlos Santana “Supernatural” record album cover. A bench encourages people to settle down and listen to the trickling water. Primack takes a seat. “I love sitting here,” she says.

She doesn’t sit for long. She has plenty to do both in and out of the yard. As a certified Master Gardener and a Master Food Preserver, she volunteers to teach at low-income schools. She also organizes garden tour fundraisers to benefit the Claremont Community Foundation, and volunteers at the Los Angeles County Fair, where this summer she’ll demonstrate a solar dehydration device that harnesses the sun’s natural energy in order to dry fruit.

After the private tour is over, before heading off for the day Primack kneels down next to some lime-green Echeveria, pushes her hands into the soil and yanks free some wilted leaves.

Ranching a Volcano, Part 1, Kaupo Ranch, Maui — The Furrow Magazine

Photos & story by Laura Read

One April morning on the Hawaiian island of Maui, the manager of Haleakala Ranch, Greg Friel, and his son and grandson saddle up to herd cattle from one lush pasture to another. Eight thousand feet above them looms the mountain’s crater, invisible among frothing clouds; two thousand feet below, the Pacific Ocean sparkles under sunny skies to the horizon.

Meanwhile, 16 miles away, the manager of Ulupalakua Ranch, Jimmy Gomes, is driving southward on the mid-mountain Pi’ilani Highway. He emerges from a bucolic forest onto terrain that looks like rural southern Italy, then enters territory that’s drier still — a bed of hard basalt lava that spilled thousands of years ago from cracks in the earth. Gomes follows the road through more greenery where it dips to the ocean’s edge. He parks at Kaupo Ranch, where manager Bobby Ferreira has gathered some prized Angus derivative bulls to sell. The two make a deal.

Around the bend northward from Kaupo lies one more of Maui’s largest ranches, this one in radically different terrain, where waterfalls and foliage flourish in deep gorges under constant rains. Hana Ranch manager Josh Daniels is pioneering a business model he hopes will sustain both the ranch and the local families who depend on it.

Friel, Gomes, Ferreira, and Daniels work within a few miles of each other, yet their operations differ so much they might as well be a few states apart. The reason: the giant dormant volcano that makes up 75 percent of the island. In this three-part series, The Furrow looks at how ranches located on different aspects of the “House of the Sun” survive.

Kaupo Ranch — Maui’s wild west

Few people realize that Hawaii — as famous for its sugar and pineapple as for its luscious beaches — is also cattle country. It has been ever since 1793 when the British explorer George Vancouver shipped a small herd — seven cows and two seasick bulls, according to a history from the Hawaii Department of Agriculture — from Alta, California as a gift for the king. Today, about 760,000 acres of the state’s 4.2 million acres are in pastureland — comprising 83 percent of all productive agricultural land in the state, according to a University of Hawaii study published in 2015.

Maui’s ranches are cow-calf operations, with permanent herds producing calves for sale to be raised, finished, and slaughtered for beef. Maui once had its own finishing feedlots and slaughterhouses, but the lots closed in the early 1990s when the costs of imported feed soared. Ranchers adapted by working with cargo shippers to send calves to the U.S. mainland for finishing and slaughter. Some 60 to 70 percent of calves annually are weaned at 6 to 10 months of age and transported to the mainland, where some are sold to be feedlot grain-finished, and a smaller percentage are finished by grass or grain on farmland owned by the Hawaii-based rancher.

While many island ranches have sold off portions or subdivided, a few properties haven’t changed much. Kaupo Ranch is famously one of the least altered.

Far Out: The property is part of a larger area that gets its name from Kaupo Gap, a rift in the mountainside that opened during a landslide more than 100,000 years ago. The slide shoved massive amounts of earth and soil onto an area where the ranch now operates, according to Ferreira. The rugged land feels remote and wild, a world away from the tableaus of resorts and sugar cane fields that travelers see on the rest of Maui.

Early Polynesians divided the land economically into wedge shapes known as ahupua’a that extended between valley ridges from the crater through to the ocean. The divisions gave early family groups access to various resources at different elevations, including sea life, timber stands, fresh water, and arable land. Kaupo Ranch still holds most of its original shape, according to Ferreira.

“It’s a tough place,” he says. “The number one reason it has remained intact is its location, and number two is the difficulty with the type of terrain. It’s very humid, and it’s all mountains. You can compare Kaupo Ranch to Haleakala Ranch — Haleakala is steep, and it is on lava; but it is close to town. When equipment breaks down, all they need to do is run downtown and come back. At Kaupo, we have 1.5 hour’s drive each way.”

Ferreira is known widely for his work pioneering an Angus Plus derivative species well adapted to mountain tropics. (Angus Plus are Bos Indicus/Angus derivatives, combining a minimum of 50 percent Angus with a floating percentage of Brahman, Ferreira says.) He also won recognition recently for transitioning the pastures of a previous ranch from fallow sugarcane fields to legume-grass mixes that support productive forage finishing. At Kaupo, he oversees 1,300 head of cattle; because of recent drought conditions, that number has been temporarily reduced from the ranch’s carrying capacity of 1,800 head, he says.

Wind and Rain: It’s hard to imagine that a tropical place like Hawaii experiences droughts. The archipelago lies in the northern portion of the equatorial zone, where prevailing northeast trade winds deposit moisture in highly localized patterns. When the winds — after traveling many miles across the ocean — reach Haleakala, they split and stream around the mountain like currents of water.

According to University of Hawaii meteorologist Pau-Shin Chu, trade winds have been diminishing recently and shifting slightly from north to east. Between about 2007 and 2013 they delivered significantly less water to Maui and the other islands in the Hawaiian chain. That was followed by a year that delivered closer to normal rain, but then that was followed by the current El Nino cycle and less rainfall on the islands. It’s been an alarming trend, Chu says. “We’ve seen this decreasing trend over the past 40 years, since the 1970s,” he says.

Where and when the rain falls depends on the property’s mountainside location and its exposure to the winds. On north- and east-facing slopes, trade winds deliver as much as 200 inches a year; on the southern or lee sides, the rain is blocked by Haleakala, and the ranches tend to receive much less, Chu says. Kaupo is on the lee side.

“Kaupo spans three miles,” Ferreira says. “We’re on the edge of the turn. I can have rainfall as high as 59 to 60 inches or as low as 17 inches. My records show that the lowest average is about 12 inches.”

But Kaupo benefits from a second wind effect. While the trade winds dominate 70 to 80 percent of the year — most prevalent in summer — another wind pattern, the Kona, supplies light moisture from the opposite direction, south and southwest, during the fall.

Another factor affecting Kaupo and the other Haleakala ranches is elevation. Air temperatures change as the volcano’s slopes rise. Grass is available year-round at one elevation or another, but different species are associated with different heights. Lower slopes grow tropical grasses and legumes, while higher sections grow a mix of tropical and temperate zone species.

Only a small number of tourists make the drive all the way around the volcano to Kaupo. When they reach the little community, they see scattered houses, a church and a single general store. The ranch and the store are Kaupo’s primary employers, Ferreira says, providing jobs for fewer than a dozen people.

The ranch’s owners include the daughter of the man who bought the ranch in 1929, William Dwight Baldwin, himself a descendent of missionaries who arrived on the island in the 1830s. The current consortium of owners is planning to continuing its traditions, Ferreira says.

“They want to preserve the lifestyle, the way it’s been out here,” he says. “The land is basically only good for this purpose. They want to know that their grandchildren are going to be left with something that they kept alive. That goes for all of us — not only Kaupo’s owners, but all of the ranchers on Maui.”

Ranching a Volcano, Part 2, Haleakala Ranch, Maui — The Furrow Magazine

Photos & story by Laura Read

One April morning on the Hawaiian island of Maui, the manager of Haleakala Ranch, Greg Friel, and his son and grandson saddle up to herd cattle from one lush pasture to another. Eight thousand feet above them looms the mountain’s crater, invisible among frothing clouds; two thousand feet below, the Pacific Ocean sparkles under sunny skies to the horizon.

Meanwhile, 16 miles away, the manager of Ulupalakua Ranch, Jimmy Gomes, is driving southward on the mid-mountain Pi’ilani Highway. He emerges from a bucolic forest onto terrain that looks like rural southern Italy, then enters territory that’s drier still — a bed of hard basalt lava that spilled thousands of years ago from cracks in the earth. Gomes follows the road through more greenery where it dips to the ocean’s edge. He parks at Kaupo Ranch, where manager Bobby Ferreira has gathered some prized Angus derivative bulls to sell. The two make a deal.

Around the bend northward from Kaupo lies one more of Maui’s largest ranches, this one in radically different terrain, where waterfalls and foliage flourish in deep gorges under constant rains. Hana Ranch manager Josh Daniels is pioneering a business model he hopes will sustain both the ranch and the local families who depend on it.

Friel, Gomes, Ferreira, and Daniels work within a few miles of each other, yet their operations differ so much they might as well be a few states apart. The reason: the giant dormant volcano that makes up 75 percent of the island. In this three-part series, The Furrow looks at how ranches located on different aspects of the “House of the Sun” survive.

It’s a Thursday morning in April, and Haleakala Ranch Manager Greg Friel, his son Cody, and his grandson Eli are on horseback driving cattle to a new pasture near the town of Makawao, Maui in Hawaii. Above them, rich green fields and native forests rise almost 8,000 feet toward Haleakala Volcano’s 10,000-foot-high crater. Below them, the volcano’s lower slopes spread 2,000 feet down to the ocean. The location could be a Hollywood movie backdrop, but it’s not; it’s just a normal background at Maui’s oldest family-owned cattle operation.

The 29,000-acre Haleakala Ranch has appeared often enough in print media and as backdrops in TV ads that its scenery may be familiar even to people who haven’t visited Hawaii. Many Maui tourists visit ranch property as part of their stay: there are zipline rides, a lavender farm and a protea farm, run by lessees, as well as horseback rides. The ranch once included a place that most everyone on the island goes to at least once, the Haleakala National Park, which surrounds the volcano’s crater. The land was swapped in 1927 with the Territory of Hawaii in exchange for agricultural lands elsewhere on the island.

Sensitive to its role in Maui’s history, managers of the for-profit enterprise strike a fine balance between tradition and innovation.

Cattle for the King: Haleakala Ranch was incorporated 1888, but cattle had been present on the islands for 95 years by then. In 1793 six cows and a bull had arrived by ship as a gift from British Captain James Vancouver to King Kamehameha I. The animals were descendants of Andalusian cattle that had been imported to the New World from Spain 270 years earlier. During the next few decades the cattle multiplied and ran wild, destroying property and becoming a nuisance. In 1832, King Kamehameha III brought in Mexican vaqueros from California to show the locals how to herd the animals on horseback. The vaqueros referred to themselves as Espaniolo (meaning “Spanish”), and the Hawaiian cowboys eventually called themselves an iteration of that word, Paniolo. Adapting their methods to the tropical resources and terrain, they developed specific traditions that survive today.

Ranching on private property in Hawaii didn’t come about until the mid-19th century. Before then, island resources were shared according to a communal land tenure program that divided land into pie shapes extending from crater to ocean. In 1848, that program was suspended in favor of a private property system that made agricultural land available for sale. Early owners of Haleakala Ranch were the grandsons of Christian missionaries who came to the island 18th century. Today the same family runs the ranch in the form of a family corporation of more than 110 members.

Ranchers bolstered the original Andalusian stock with imported Aberdeen Angus and Ayrshire breeds, and later Holsteins and Herefords, according to the writer John Harrison, who explored the ranch’s history in his book “Haleakala Ranch,” published for the ranch’s 125th anniversary in 2013. “We’ve been breeding black and red angus, picking them by body type, looking at moderate framed animals which means they don’t get very tall,” Friel says. “We want them to be easy fleshing — not animals that take a lot of input to keep them in good condition.”

Friel was hired by the Baldwins as ranch manager in 1994. He had previously managed another large ranch, Hana Ranch, on the other side of the island. Friel filled big shoes, not the least of which belonged to a legendary manager of nearly 80 years earlier, Louis von Tempsky. Harrison wrote about Tempsky: “Von worked tirelessly to improve the ranch’s stock — cattle, horse, pigs, and sheep…. His meticulous records, still held by the ranch, bear witness to the thousands of trees he planted across the ranch lands to improve the watershed. He experimented with planting different types of wood for a variety of uses: fence post, firewood, railroad ties, building lumber, and so on. He introduced different grasses to improve the feed and cultivated a wide range of diversified agricultural crops in the hopes of developing businesses for the ranch other than cattle. Among these endeavors were plantings of corn, vegetables, castor oil beans, pigeon peas, sisal and various grass crops. Another crop grown on the ranch during Von’s stewardship was pineapple— a business that was to benefit the economy of Maui and create thousands of jobs over subsequent decades.”

A century later, some of Friel’s concerns are similar, however ranching now is more costly and more complicated, even while new technology and information sharing make creative solutions more accessible than ever before.

Around the Slope: Like von Tempsky, Friel is an innovator. One of the challenges he faces — a surprise on a tropical island known for waterfalls and palm trees — is drought. The ranch properties wrap around different sides of the volcano, and slopes facing different directions get varying amounts of rain depending on their relationship to the northeast trade winds, which bring most of the island’s moisture. So parts of the ranch are extremely wet, and parts are arid. “There’s no average,” Friel says. “It depends on elevation, exposure, and winds. In a good year we’ll get 8 inches on the ranch above Kihei, while over in the forest we’ll get 60 inches. It’s very diverse within a span of ten miles.”

There have always been drought cycles, but a recent 6-year drought, followed by a wet year and then another dry year, was tough. With meteorologists suggesting the drier weather patterns will continue, Friel is working on drought proofing the ranch. “My best guess is to plan for it to be drier,” Friel says. “If it’s not drier we’re ahead of the game. If it is dryer, we’re prepared.”

Drought proofing includes adjusting the ongoing forage program. “We’re trying to introduce some new forages to help get more diversity for the animals, and for the health of the pastures —a mix of grasses, legumes, and some flowering plants,” Friel says. “The more variety you have, the more root system layers develop in the ground, making for a better balanced and healthier stand of forages. The dry weather makes it a little bit rough to get them established.”

The drought forced herd reductions, but the ranch is now restoring numbers to the capacity of 1,600. “We’re keeping the heifers back to build the numbers back up,” Friel says. “We are just a shade under 1,000 now.”

Diversifying product is also on the table. Haleakala has 1,800 goats, which are used for foliage management and as a meat source for some islanders. Sheep numbers are tied to what the island’s sole slaughterhouse can handle. “If we get the stability in the slaughterhouse, then we might go to 1,000. Right now we have less than 350,” Friel says. And there are chickens. The ranch has a new stock of layer hens, but it’s important to find a local byproduct to feed them so the ranch doesn’t have to pay costly prices for importing feed to the island. “In Hawaii we don’t have a lot of ag byproducts, so we keep investigating,” Friel says. “We would like to find something that would open us up to the production of meat birds instead of just layer hens.”

The drought’s impact on forage is magnifying another problem, the invasion of axis deer, which were brought to the island years ago for game hunting. Hunting has not kept the wandering ungulates in check, and now, like the cattle delivered by Captain Vancouver long ago, the deer are wreaking havoc, eating up the forage the ranch is managing so carefully for its own animals. “They’re having an impact on our fences and our grazing management,” Friel says. “When we rotate the cattle out of pastures, the cattle might not return to that area for 90 to 120 days, but we can’t control the deer from going in.” Ranchers are working with the State of Hawaii to find a solution, but so far there’s been no easy fix.

Tradition Passed Down Is Friel’s son Cody going to be a rancher like his dad? It’s likely, since he’s already in charge of one of the ranch’s quadrants. Are the grandkids headed that way? That remains to be seen, says Friel.

It’s highly likely that Paniolo traditions will continue. Although most of the Paniolo have traded cowboy hats for ball caps, they are still seen at brandings and elsewhere using original tools and techniques on horseback. Hawaii has attracted people of many different ethnic origins, including Japan, Portugal, and China. Cattle ranches like Haleakala are exciting places to witness an elegant blending of the old with the new.

Ranching a Volcano Part 3, Ulupalakua Ranch, Maui — The Furrow

Photos & story by Laura Read

One April morning on the Hawaiian island of Maui, the manager of Haleakala Ranch, Greg Friel, and his son and grandson saddle up to herd cattle from one lush pasture to another. Eight thousand feet above them looms the mountain’s crater, invisible among frothing clouds; two thousand feet below, the Pacific Ocean sparkles under sunny skies to the horizon.

Meanwhile, 16 miles away, the manager of Ulupalakua Ranch, Jimmy Gomes, is driving southward on the mid-mountain Pi’ilani Highway. He emerges from a bucolic forest onto terrain that looks like rural southern Italy, then enters territory that’s drier still — a bed of hard basalt lava that spilled thousands of years ago from cracks in the earth. Gomes follows the road through more greenery where it dips to the ocean’s edge. He parks at Kaupo Ranch, where manager Bobby Ferreira has gathered some prized Angus derivative bulls to sell. The two make a deal.

Around the bend northward from Kaupo lies one more of Maui’s largest ranches, this one in radically different terrain, where waterfalls and foliage flourish in deep gorges under constant rains. Hana Ranch manager Josh Daniels is pioneering a business model he hopes will sustain both the ranch and the local families who depend on it.

Friel, Gomes, Ferreira, and Daniels work within a few miles of each other, yet their operations differ so much they might as well be a few states apart. The reason: the giant dormant volcano that makes up 75 percent of the island. In this three-part series, The Furrow looks at how ranches located on different aspects of the “House of the Sun” survive.

Highway 37 ascends gradually from Kahului Airport on the north coast of Maui, Hawaii up the slopes of the island’s largest volcano, Haleakala. Un the region around 2,000 feet elevation, it enters communities where the island’s permanent population has chosen to settle – cooler areas removed from the island’s busy beaches and harbors. As it ventures southward toward the volcano’s more remote leeward side, the highway touches sites that mark stages of the island’s cultural history: the octagonal Holy Ghost Mission, built in 1894-95 for Portuguese sugar plantation workers; Grandma’s Coffee House, which began roasting coffee in 1918; the 21st century retreat of Oprah Winfrey; and finally, the headquarters of Ulupalakua Ranch, where people from all over the world come to experience how one of Maui’s most innovative families is finding new ways to pair the the nuts and bolts of agriculture with the people it serves.

Ranch Heritage Farming at Ulupalakua – at 18,000 acres Maui’s second largest ranch – goes back 175 years through six different owners. From the native “poi economy,” which produced taro, sweet potatoes and other crops, through sugar production and the raising of livestock, the ranch’s changing tactics reflect Hawaii’s evolution of modern ag.

In the 1840s, the poi economy started to recede when King Kamehameha III and his advisers argued that an economy of commercial agriculture would be a stronger driver of the island’s future. In 1845 Captain Lincoln L. Torbert leased land in Ulupalakua to produce beef, hogs, sheep, sugar, molasses and Irish potatoes. But sugar operations all over the islands faltered as land prices, taxes and competition grew, and in 1856, a retired sea captain, James Makee, bought the Torbert Plantation and changed its name to Rose Ranch. His approach to sugar was successful: For a decade his mill produced 800 or more pounds of sugar per year on 1,000 acres. Makee had broad ideas: Capitalizing on lovely views, he planted exotic gardens, built cottages, and started what was perhaps Hawaii’s first ag-tourism project — a festive retreat that became popular with royalty from the islands and visitors from around the world.

The ranch’s next owner, James Isaac Dowsett, who held the property from 1886 to 1900, improved the cattle herd by bringing Aberdeen Angus stock to the islands. Dowsett sold to Dr. James M. Raymond, who in 1922 sold to Frank Baldwin, the grandson of Maui’s first Christian missionaries. Baldwin renamed the place Ulupalakua Ranch. Today’s operation began in 1963 when C. Pardee Erdman bought from the Baldwins. The Erdman family revived Makee’s enterprising spirit, but in a different direction, developing the property into a favorite destination for both travelers and locals.

One of the first buildings that visitors see when they arrive is the colorful Ulupalakua Ranch Store & Grill. Incorporating new ideas about serving fresh food, the Erdman’s brought in executive chef Will Munder, who fills the Grill menu with produce harvested locally and lamb and elk raised on the ranch. “Munder thinks outside of the box,” says Jimmy Gomes, Ulupalakua Ranch Manager. “He’s put some delicious meals on the menu that the store has never sold before. What we have now is word of mouth. People are saying, ‘You need to go to the ranch to taste the food.’”

A visit can start with one of the daily estate tours that begin at a small museum. Photos of early ranch life show how Paniolo, Hawaii’s distinctive cowboys, escorted cattle through the water from Makena Landing to waiting skiffs that took the animals to cargo ships bound for the U.S. mainland. Makena Landing is now a public park.

Guests also can see enormous trees surviving from Makee’s ownership and a hula dance performance ring where Makee helped revive the island’s ancient form of storytelling. They explore facilities for making pineapple-wine, and finish the tour at a wine-tasting bar inside the same cottage where King Kalãkaua and his wife, Queen Kapi’olani, spent many a festive evening in the late 19th century.

The tasting experience introduces much more than the ranch’s famous pineapple wine. In 1974 the ranch partnered with Emil Tedeschi, of Napa Valley’s Tedeschi Family Winery, to develop vineyards and new wines suitable for the tropics. Today, the vineyards produce Malbec, Syrah, Grenache, Viognier, Gewürztraminer and Chenin Blanc grapes. Wines from the ranch are distributed to many U.S. states and to four countries around the world.

Into the Outback Beyond the headquarters, Highway 37 extends south, southwest and then eastward across Haleakala into famously isolated leeward terrain. As the land plummets to dry coastal areas and rises to cooler forests at 6,500 feet elevation, it’s easy to see how Ulupalakua Ranch covers a remarkable range of 10 microclimates. Far below, at the shoreline, condominiums and four star resorts rise from land that Ulupalakua once owned.

This part of the ranch also hosts one of the island’s more startling scenes: Eight massive wind turbines that pin-wheel at “Star Wars” heights into the cobalt sky. The project was quite controversial when Ulupalakua first leased the land to Sempra Energy. The 3-meg turbines can power 10,000 homes, Gomes says. “We have income we never had before. It affords us to keep open space.” Sometimes cattle can be seen clustered in a corral near the turbine’s bases.

Further along the highway, the earth splits and the guts of Haleakala— rifts of chunky volcanic rock — spill in a vertical seam to the sea, a reminder of how the first of the Hawaiian Islands emerged 30 million years ago when a pool of hot magma began seeping out of cracks in ocean floor, according to the United States Geological Survey. As ocean’s tectonic plate shifted, the emerging magma hardened in the cool water and built up in layers. Over thousands of years, more islands were born. Haleakala began its undersea life 1 to 2 million years ago. There are still active volcanoes in Hawaii, and active underwater vents are building new islands, but the USGS says the youngest of these won’t reach the ocean’s surface for another 30,000 to 100,000 years.

Cultural change has been quite a bit more volatile than geology in the past few hundred years, starting in the 12th century when Polynesians navigated to the island, and moving through the arrival of new ethnic groups that included Euro-Americans, Portuguese, Chinese, Japanese, and African Americans coming as laborers, missionaries and businessmen. Livestock producers have adapted by pooling all the tools, technologies and materials available to them. As one of the Ulupalakua tour guides likes to say, “The Erdmans are fixers.” They are visionaries, too.

“You can’t just survive only on cattle,” Gomes says. “We’re looking at new projects — aquaponics, tea, and alternative crops. We’ve started a koi seed orchard and we have goats and sheep for weed control. We’ve had a dry land reforestation project for the last 20 plus years, which has all been planted with native plants. All of these things will help us improve our bottom line.”

Wouldn’t the bottom line be stronger if the ranch converted its scenic acres into resorts, a person might ask. The owners would rather preserve Hawaii’s ag tradition, Gomes says. “It’s the lifestyle that we want to perpetuate,” he says. “We want to be the best we can, and with that in mind we protect our natural resources, whether they be our spring water, the vegetation or the native plants. We want to be good stewards, diversify and continue employing people who love being in Hawaii.”

Alaska's Williams Reindeer Ranch — The Furrow

Photos & story by Laura Read

THREE YEARS AGO, Denise and Josh Hardy were living in Spokane, Washington, with their four children when they got a call from Denise’s mom and dad, Gene and Tom Williams, who live on the family farm in Alaska.

The parents asked their daughter and son-in-law to move home and take over the family livestock business — raising not cattle or sheep, but reindeer. The answer was clear to Denise. Of course.

With their kids in transition between schools, the Hardys moved in with Grandma and Grandpa. Josh kept his full-time job as an adjuster with Safeco Insurance; Denise assumed responsibility for the reindeer farm’s tourism program.

“Tom had always dreamed of having one of his children run the farm,” Josh said. “The timing worked out well.”

What happened then was a nothing short of a reindeer revival.

The place of Denis’s childhood is a 1930s dairy farm built by in a New Deal program that moved settlers from the American Midwest into Alaska’s fertile Matanuska-Susitna Valley. The settlement was called the Matanuska Colony. Located in wide river-bottomland surrounded by high mountain peaks, it was also the kind of place where Santa Clause liked to appear occasionally outside of Christmas. Denise was not about to let it go.

The deer had been part of Denise’s life since 1987, when her dad arrived home from Canada with a semi-truck full of 19 reindeer. The thought of owning reindeer had captivated Tom Williams since high school. After starting a law practice in Anchorage, he finally had his chance to buy some. He developed the family ranch as a learning center about his so-called “cattle of the north.”

Improving a good thing: One of the Hardys’ first actions as managers was to redo the barn.

“It’s still the barn where Tom milked cows when he was a kid,” Josh explained, “but we’ve added to it. We have a heated area so food doesn’t freeze in winter. The original chicken coop is now our gift shop. I know that it’s original, because when I cleaned it out, it had original Matanuska Colony chicken poop in it.”

They extended the tourism season with an October Festival and a Christmas extravaganza, which featured elves, Santa, and a 15,000-light and music show.

Their dad had already started a whacky annual spree called the Running of the Reindeer held during the Anchorage Fur Rendezvous in homage to the Running of the Bulls event in Pamplona, Spain. As onlookers cheer, reindeer stampede down city blocks chasing participants who run for the lives.

Explaining the breed: The changes worked, and now the Williams Reindeer Farm sees thousands of visitors a year. All three of Tom’s daughters and their families get into the action. As tour guides, usually Denise or one of her sisters, Wendy and Kim, is the guide explaining that reindeer are domesticated cousins of the wild caribou. Their outer fur layer is hollow, which increases insulation and makes it easier for them to swim. The deer have two big toes in the front of their hooves, and two dew claws in the back. They have four stomachs, and it takes them 20 hours to digest their food. In summer, their antlers are coated in a sensitive velvet fuzz. The velvet sheds in fall, which leaves the antlers scarlet with blood for a few days before the bones turn white. Males lose their antlers in fall. Females keep theirs until after Christmas, which means —sorry kids — Rudolph is really a Rudolphina.

Sorting by niceness: Leading the tours is fun, but there’s also serious work to be done. About 160 reindeer live on the farm. Last year, 70 calves were born. In spring, the animals are sorted according to temperament. The friendliest join the “show herd”; the less friendly get to enjoy life out in the fields for a while. In late summer, the whole herd is sorted for breeding, slaughter and sales. Some are sold for sleigh ride operations or to exotic animal collectors. Last year, some went to an animal movie star company in California. Females can sell for up to $3,000.

The deer are vaccinated and tested regularly tuberculosis, brucellosis and chronic wasting disease, Denise said.

For help, the Hardys hire six summer employees. They hire another 25 people during the busy fall festival. A couple of employees work year-round to help manage the herd. “They are the lucky ones who feed during all temperatures, even when they reach- 40° in winter,” Denise said.

Visitors: Daily summer tours cost $8 for adults and $6 for kids. Visitors learn what reindeer eat, how their tendons click when they walk, and how the velvet-covered antlers are extremely sensitive. “I have seen a mosquito land on an antler, and the animal can feel it,” Denise said. “If they hit their antler on something, it hurts them.”

After the presentation, visitors mingle with the reindeer carrying plastic cups full of pellets made of barley, fish, soy meal, molasses, vitamins, minerals and salt. (The reindeer also eat grass, grain, and hay grown on another farm Williams owns near Anchorage.)

Daily visitor counts total anywhere from 90 to 250 in summer, Josh said. The October Festival brings in a couple of thousand people, and Christmas draws another few thousand. That’s when Josh climbs into a red suit and adds Santa Clause to his repertoire.

“I get to be a very benevolent person for about two weeks out of the year,” he said. “I love it.” Kids love it, too.

The whole farm: The Hardys provide more than just reindeer attractions. In addition to the elk, there are horses, rabbits, chickens, a bison, and a tame moose named Denali. The more fearless of visitors feed Denali by holding out carrots with their mouths. The sight makes everyone double over with laughter.

The good feelings are not lost on the Hardys.

“You have moments of absolute beautiful glorious peace, here,” Josh said. “The rest is hard work. The minute you’re done fixing and correcting and nurturing, then the next problem hits, and you just keep going. That’s the challenge of the American farmer, to adapt and overcome. If we can do it with reindeer, you can do it with anything.”

All Photos Copyright Laura Read

Saving the Family Farm

San Francisco Chronicle Magazine

THE NECTARINE'S SKIN wrinkled into folds, releasing the sweet-tangy flesh underneath. Before the juice could dribble, I sucked it into the pockets of my cheeks and savored its goodness. I ate another. Afterward, I telephoned Twin Peaks Orchard, near Newcastle in Placer County, 75 miles away from my home in north Lake Tahoe. “I need a whole case of these nectarines,” I said. I would be driving to San Francisco the next day; owner Sheila Enriquez agreed to meet me at the orchard on my way.

A few years ago, I didn’t know a person could easily buy fruit directly from regional farmers. At the same time, many farmers in Placer County, which extends from just outside of Sacramento to north Lake Tahoe, didn’t know there existed scores of people who would pay more for better tasting fruit fresh off the tree. In the late 1990s, they were in turmoil. Experiencing shrinking profits and expanding development pressure, family farmers were selling out. In five years, one sixth of Placer County’s farmland vanished under new neighborhoods and malls. In 1997, 35 percent of Placer County’s farmers were 65 years or older and ready to retire. Half of all farmers reported having no family members around to take over the farm.

What happened next could be called a lucky intersection of forces — a message, a woman and a moment. Things in Placer County reached a tipping point, to borrow the term from Malcolm Gladwell’s book of that name.

From I-80, the route to Twin Peaks curves along stone-knuckled ridges, riverbeds and hollows that typify this section of the northern Sierra Nevada foothills. In June, fields of grass were already turning gold, their drying stalks releasing a smell of roasted wheat that seeped into my car’s air system. At Twin Peaks Orchard, Enriquez greeted me with a hand that felt warm to the bone. Inside the barn sat my box, its 60 nectarines resting in neat plastic liners, blushing lightly.

I reached for one.

“You don’t need to squeeze them,” Enriquez said, the punchy cadence of her speech mimicking the rhythms of the landscape. “Everyone wants to squeeze them. You can tell they are ripe just by brushing them with your finger.”

I pressed the skin of one. It felt cool and silky. I still wanted to squeeze.