Thinking Big at Bently Ranch - The Furrow

Photos & story by Laura Read

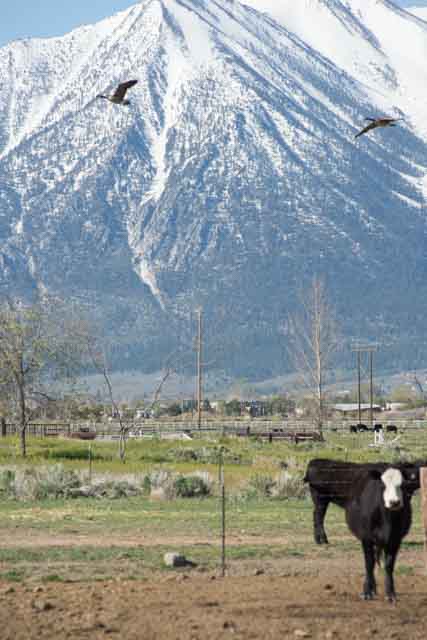

CARSON VALLEY, NEV. IS NAMED for Kit Carson, the 19th century trapper and scout who guided John C. Freemont on his 1840s explorations of the American West. The valley spans 14 miles between the granitic bulk of the Sierra Nevada and the high desert curves of the Pine Nut Range. At its heart is the Carson River, which originates on the slopes of California’s Sonora Peak and – flowing improbably away from the Pacific Ocean – ends in the Nevada desert, where it sinks into the earth.

Today, a new kind of advance guard is at the helm of one of the valley’s largest ranches. Christopher Bently, 48, took over running Bently Ranch in 2012 after his father, the inventor and electrical engineer Donald E. Bently, who was running it as a beef cattle ranch, passed away. The ranch now includes about 65,000 acres located in four western regions: in Carson Valley, near Lovelock, Nev. and near the towns of Bridgeport and Red Bluff, Calif. While Carson Valley has felt the nip of new housing at its edges, much of its center has remained open – quite a bit of it devoted to cattle ranching and wetlands preservation. The younger Bently wants to continue the ranch’s heritage, but he also wants to grow it in a new direction: Next year he’ll open Bently Heritage Estate Distillery inside of restored 1906 mill and creamery buildings in the town of Minden, population 3,000. The distillery will produce gins, vodkas, whiskeys, and other specialty spirits. Most of the ingredients will be grown right on the ranch.

“This has been a hard-working ranch for a lot of years,” Christopher Bently says. “It is my goal to protect as much open space and as many beautiful historic properties as possible so that we may retain our environment and culture for future generations.”

Heritage: Bently’s plan is rooted in the legacy of his father. In 1960, Don Bently, then a 36-year-old electrical engineer from San Francisco, bought some acreage in one of the valley’s oldest ranches. Established by the German immigrant H.F. Dangberg in 1857, the Dangberg Ranch filled a portion of the northern end of the scenic valley corridor along U.S. Route 395 south of Reno and Carson City. Comfortable thinking outside of the box (one of his alma maters, the University of Iowa, called him a pioneer and a visionary), Don Bently saw in the section that he bought, a way to combine the two driving forces of his life: his ground-breaking engineering work, and his respect for agricultural landscapes.

In the beginning, he built a laboratory and headquarters for the research, development, and production of his inventions. Eventually the Bently Nevada Corporation became a $200-million-per-year manufacturer of his ground-breaking electronic systems used to monitor the mechanical conditions of machinery.

It wasn’t until 30 years later that Don Bently turned more attention to agriculture. In 1997, after slowly acquiring a total 35,000 acres of the Dangberg Ranch, he established Bently Ranch to raise beef cattle and alfalfa. As he reduced his ranch’s energy footprint and restored its natural wetland systems, the ranch was lauded by many observers as an example of sustainability.

Fermentation: When Don Bently died, Christopher was head of the San Francisco-based Bently Enterprises, known for its LEED-certified (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) renovations of significant structures like San Francisco’s old Federal Reserve Building. The younger Bently had grown up in San Francisco with his mother after his parents divorced. He loved the tradition and purpose of the ranch, and he loved Carson Valley.

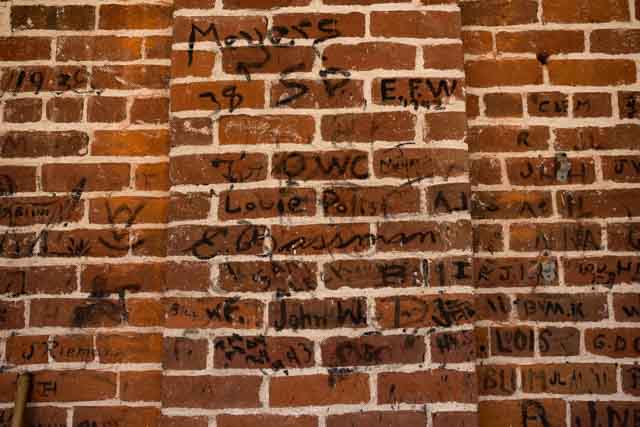

Having as a kid prowled the old empty ranch buildings on his family’s property, Bently is fond of their contributions to the area’s historic character. In the town center, during the first years of the 20th century, the Dangbergs had developed the Minden Flour Milling Company and the neighboring Minden Creamery; both are now listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Bently had a strong desire to build a distillery, and saw opportunity in a boom of independent distilleries taking off across the world.

He and his team proposed restoring the old brick flour mill and creamery, installing state-of-the-art equipment, and opening Bently Heritage Estate Distillery.

Changes started in the ground. General Manager Matt McKinney replaced some alfalfa fields with four kinds of barley and seven types of grain, including rye, corn, triticale, hulless oats, and spelt. He set about identifying heritage grains good for alcoholic brews and spirits.

Because breweries were multiplying in regions nearby, ranch managers began looking at growing hops. (There are 623 small breweries in California and 37 in Nevada, according to the Brewers Association — at least 25 of the Nevada facilities sit between the cities of Reno/Sparks and Carson Valley.) A total 1,500 hops of different varieties were planted — including chinook, centennial, and cascade. “They take 30 percent less water than legumes and alfalfa,” says Woody Worthington, ranch operations manager. This year, the ranch finished building a 20,000-square-foot malting and grain processing facility that includes 200-, 400- and 2,500-ton silos.

The additions fit Christopher Bently’s commitment to sensitive animal husbandry practices. “It is imperative that we conserve natural resources,” he says, “and that we have complete control over how the animals are raised and brought to the consumer, while ensuring that our cattle don't have a negative impact on the surrounding countryside.”

Herds are moved to fresh pastures as needed in order to maintain grass health, and cattle are allowed to grow at a natural rate rather than being fed to speed weight gain, Bently says. The ranch uses solar energy when possible, and recycles organic materials into compost, according to Worthington.

Field to Flask: As for the mill and creamery compound, which occupies a couple of Minden blocks, renovations have been dramatic. In 2014, with the help of the Nevada State Historic Preservation office and an industrial archeologist, about two dozen pieces of machinery were cataloged and photographed. Floor plans were made showing the locations of the old machinery inside the building, according to Bently. Some of the stored machinery will be on display once the finished building is open to the public next year.

The mill renovation included installing floors and catwalks inside the three-story grain silos for access to a new mash tun (which converts starches in crushed grains into sugars for fermentation), as well as fermentation tanks and handmade stills from Scotland. These will produce a Bently Heritage single malt whiskey. The creamery building will hold German-made stills to produce Bently Heritage vodkas and gins. All ingredients will be ranch grown, Worthington says.

Thinking forward: What people in the tasting room may not realize is that, even as Bently is making his ideas a reality, he’s inspiring the next generation of entrepreneurs. As the estate distillery readies to open, research and development percolates inside of a smaller “incubator” facility nearby where food chemists, distillers, and other creative problem solvers are concocting new alcoholic spirits formulas. They often collect flavor ingredients by prowling the high desert, plucking shrubs, flowers, and grasses they hope will ultimate taste divine.

“I’m a big believer of letting people do their jobs,” Bently says. “We have an incredibly talented pool of people who are all part of this. It’s fun to see people excel. They have great ideas.”