Winnemucca to the Sea Road Trip - VIA Magazine

VIA Magazine

In the 1950s, ranchers in northern Nevada dreamed of having a straight-shot drive to the California redwoods, where trees soar to the clouds and the ocean mists cool the air. But they were thwarted because the direct route west wasn’t completely paved; it took way too long to reach their paradise.

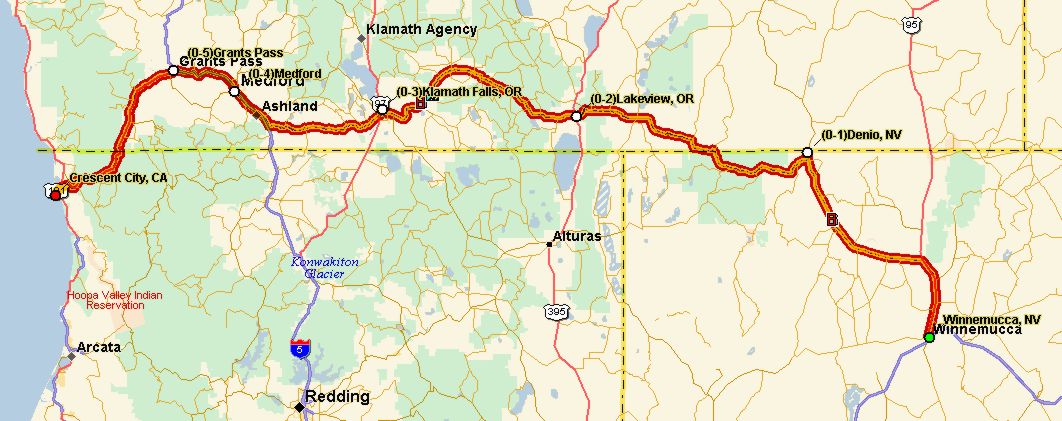

Hopeful minds went to work, and many handshakes later the fully paved Winnemucca to the Sea Highway was born. The 494-mile-long motorway never gained the acclaim its originators imagined, but today it is finding a niche among people looking for unusual ways to access the West. On two-lane roads, the route joins a handful of colorful towns to link Nevada's Great Basin vistas to the small wineries and mountain resorts of Oregon and the rugged California coast. Traveling the full length of it can take two days or two weeks, depending on your curiosity and time.

The journey begins at a bend in the Humboldt River, where the town of Winnemucca, Nevada has bloomed on the site of an early wagon train camp. A hundred years ago, Basque sheepherders migrated here to work in the nearby hills. In wintertime they took lodging at the 1898 Martin Hotel, gathering in the big dining room for meals. Today, the Martin’s menu remains the same, from starters of soup and vinegary salad, to plates of sweetbread, lamb, and rib eye — all washed down with generous carafes of wine.

The Winnemucca to the Sea Highway’s eastern segment was labeled Highway 140, and that’s where, north of Winnemucca you turn west from U.S. 95, and the hum of traffic fades as you cruise into the Quinn River Valley and its framing mountain vistas. It is land suitable for Zane Gray and the Lone Ranger — vast and silent beneath eggshell skies.

Before long, the Denio Junction Café appears in a cottonwood tree oasis. Stop for a burger and some shoestring fries, because it will be a while before you see a restaurant again. Soon, Highway 140 enters the Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge and climbs a rise near a deep crack in the earth called Thousand Creek Gorge. Follow jeep roads to the gorge’s rim, and you can stomach-crawl onto the sun-warmed rock and peer down at the stringy creek below.

Nearby is Duffurrena Ponds, where sandhill cranes and other migrating birds feed, and fishermen catch largemouth bass. This area produces fire opals; at the Royal Peacock Mine, you can sift through tailings for your own sparkling cache.

“Sagebrush is a very fair fuel,” wrote Mark Twain in his memorable chronicle, “Roughing It,” “but as a vegetable it is a distinguished failure.” The Sheldon Refuge pronghorn antelope would disagree. They find plenty of sagebrush to eat on the 900-square-mile refuge. From a distance, the tawny ungulate resembles a white-tailed deer — until it runs. Springing across the plains on slender legs, it can sprint to 60 miles per hour. Having ultra-keen eyesight, it can spot a moving critter — or your car — three miles away, so look sharp.

Pronghorn share their terrain with wild mustangs, wild burro, and bighorn sheep, whose hoofmarks pock the refuge’s dusty side roads. Lucky visitors might see a herd of bighorn sheep scrambling across the highway near Adel, Oregon. Wait a minute as they go by, and they might actually stop once they’re off the pavement and turn to stare at you.

Adel is smaller than Denio, but has a combination store, saloon, and café that is large in atmosphere. Duck inside to see vintage saddles dangling from the ceiling like chandeliers, and get a close look at taxidermy restorations of animals that wander the region.

As Highway 140 meanders through southern Oregon, big animals give way to big mountains. West of pretty Upper Klamath Lake, the volcanic summit of Mount McLoughlin lords over the southern Cascade Range. Here you can disappear among fir trees on the 9.3-mile High Lakes Trail, which is wide enough for wheelchairs. Both the High Lakes Trail and Highway 140 pass the rustic Lake of the Woods Resort, where anyone can rent a boat or, better yet, sag into a log cabin chair with a book. (instead of the book, this could say something about the bacon and eggs you get there at the lakeside greasy spoon)

Farther west, the road drops into the Rogue River Valley, where the city of Medford anchors a landscape of rolling hills and tabletop bluffs. Visit the Rogue Creamery and the Harry and David fruit store, or sip some Gold Medal Syrah or Claret at the locals’ hotspot, RoxyAnn Winery, tucked into historic Hillcrest Orchard. (http://www.roxyann.com)

The Winnemucca to the Sea Highway then joins Interstate 5, where it climbs into the sporty village of Grants Pass, a home base for whitewater kayak trips on the Rogue River (http://www.orangetorpedo.com/rogue-river-rafting), geocache excursions, or watching the hand-blown vases created by the artisans at The Glass Forge (www.glassforge.com).

When the route veers south onto Highway 199, you’re approaching the ranchers’ redwood heaven. But don’t hurry on just yet. At Cave Junction, take a detour to Oregon Caves National Monument. While prowling the twisting tunnels, you’ll likely spy a miniscule life form as fascinating as Nevada’s leaping pronghorn — the white springtail, no bigger than a snip of grass. In a feat as marvelous as the antelope’s spectacular sprint, the insect catapults itself a distance several times its body length simply by vaulting off of its tiny, folded tail.

Finally…the redwoods. Highway 199’s passage through Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park intersects paths that wind deep into the muscular beauty of these sky-bound conifers. Stout Grove is a particular gem.

Grab a strawberry milkshake at She She’s Drive-In, and then travel just a few miles more to where the road arrives at Crescent City and its endless beach. Here the Pacific unrolls its silvery waves onto the amber sand.

But the journey’s not over until you’ve had a good meal. At the Seascape Restaurant, that Winnemucca steaming plate of lamb is rivaled by heaps of sautéed scallops, oysters, and shrimp — a mouthwatering catch from the sea.

All Photos Laura Read