Secrets of Mesquite — The Furrow

Photos & story by Laura Read

The Furrow

WHEN VICTORIA OLIVARES waves a long stick of bamboo-style cane high into the branches of a wild mesquite tree, lemon-yellow catkin flowers jiggle among the leaves like pipe cleaners, and a few dried-up old bean pods flutter down to a plastic sheet laid on the ground. The legumes were plump when they were ripe last spring, but by this time in winter they’ve withered. Olivares gathers them anyway. They’ll be good for the cows.

The farmer’s wife isn’t here to collect old beans, though.

The tree is part of a mesquite woodland on the alluvial floodplain of the Rio Salado inside an extremely diverse region in south central Mexico called the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Valley. The arid and semi-arid hillsides and riverbeds here contain one of the greatest concentrations of plant and animal life in the world, although you wouldn’t guess it.

The landscape seems to support more thorns than leaves.

At another mesquite tree nearby, two of the people with Olivares, Minerva Cruz Vasquez and Richard Hanson, press their fingers into dark sap that bubbles on the trunk. They dab some of it onto their tongues, then spit in disgust. The sap tastes foul. Olivares breaks out laughing.

But there’s a part of the tree that tastes far from foul: the legumes. That’s why Cruz and Hanson are here. They’ve driven three hours from their workplace to have Olivares show how in springtime when fresh legumes hang fat and in clusters, she’ll shake hundreds of them off the tree and collect them on the ground. They’ll then be transported across the desert valley and over a mountain range into the neighboring Etla Valley, where they will be dried and milled by a new cooperative into flour.

There’s good reason for the effort: “These mesquite pods have better flavor and nutrient concentration compared to those in the central valleys,” says Cruz. She runs the new cooperative, called Xuchil Natural Foods. Not everyone believes that mesquite beans can be eaten by humans; people are used to feeding them to animals. But Cruz and her Xuchil team are betting that once people try the gluten-free, high protein flour milled from these bean pods, they’ll want to keep it on hand.

The cooperative formed in 2015 when its members — Zoraida Perez, Petronila Hernández, Antonio Garcia, and Carlos Lopez — identified existing resources (water, solar, natural edible plants), then developed a business plan. After flavor and nutrition profiling, the group determined these particular pods were of the highest quality, and once cleaned, dried, and milled would make an exceptionally delicious flour.

The tree is the Prosopis leavigata, or smooth mesquite, one of 44 mesquite species in the world, and native to not only Mexico, but also Bolivia and Peru. It is considered threatened by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. In Mexico — as in many countries — mesquite trees are often ripped out to make way for farm fields and roads. But here in this boulder-laden river bottom of the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Valley, they’ve largely been left alone. That’s good for Olivares because she’s earning a little extra income from the trees, thanks to Xuchil.

Sarahi Garcia cofounder of the nonprofit Tejiendo Alianzas

Sarahi Garcia, cofounder of the nonprofit Tejiendo Alianzas, which advises the startup Xuchil Natural Foods, agrees that a bubble of mesquite tree sap tastes foul.

Ancient farming. The cooperative’s success is linked closely to this valley. Archeologists have unearthed evidence that ancient people were cultivating beans, corn, and squash here 6,000 years ago. They’ve discovered remnants of irrigation systems — dams, canals, and aquifers — that are 2,000 years old. UNESCO listed the region for protection in 1998 and 2018, citing the value of its 36 plant communities that include more than 3,000 species of vascular plants and represent 70% of worldwide flora families. It sustains 134 animal species, 356 species of birds, 53 species of reptiles, and between 15 and 24 species of bats, according to UNESCO. The heritage of its human residents is diverse, too. They descend from seven different ethnic groups, some of which were active here 10,000 years ago.

“The semi-arid climate, access to water, and mineral rich soil are apparently what set these beans apart from the deserts in the north where mesquite grows everywhere,” Hanson says. “We know that the beans are thicker, longer, and sweeter.”

Hanson and his wife, Sarahi Garcia, founded the nonprofit Tejiendo Alianzas (the Spanish name means weaving partnerships) in Oaxaca a few years ago to connect rural start-ups in villages like Xuchil with experts who help them to succeed. In addition to the village of Santiago Suchilquitongo, where Xuchil is located, they work with communities like Santa Maria Ixcatlan, where they support palm crafting and mezcal projects, and San Dionisio Ocotepec, where they assist makers of shoes, mezcal, and chocolate. “We are active participants in marketing, promotion, product development, research, and sales,” says Hanson, who moved to Oaxaca from Texas 12 years ago. “Tejiendo Alianzas links us to many worlds, from agriculture to artisan craft, both of which are incredibly important in Oaxaca.”

Victoria Olivares showing how to harvest bean pods

Victoria Olivares shows how she harvests bean pods from mesquite trees for Xuchil near her home in south-central Mexico.

An important move for Tejiendo Alianzas was to connect Xuchil to the National Polytechnic Institute in Oaxaca. “We partnered with a professor and graduate students to identify the proper way to dry the beans in order to not lose their nutritional properties, while making them easier to mill,” Hanson says. “The sugars make the inside pulp very sticky, so drying it as much as possible makes a huge difference. We also sent the flour to a nationally certified lab to get the official nutrient breakdowns that we can put on our labels.”

Research on the human food value of mesquite is also happening in northern Mexico and the southern United States. Depending on the species, the pods can have 7 to 22 percent protein, according to researchers. They contain potassium, manganese, and zinc and up to 41 percent sugar, mostly fructose. Lab tests showed the Xuchil beans have protein levels of 19 percent.

“It is a yummy superfood,” Hanson says.

South central Mexico’s Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Valley photo

South central Mexico’s Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Valley is considered one of the world’s cradles of agriculture.

Spreading the word. Making a good flour was only half the battle for Xuchil. The other half was helping people to learn how to use it. Hanson turned to professional chefs to spread the word. Oaxaca’s culinary culture stems from its agricultural abundance. People make elaborate meals at home, and inventive restaurant chefs serve an eager community of visiting and local diners. “It’s really impactful here in Oaxaca when people can say, ‘We have this high-quality product, and it’s not only made by local people, but also made with local natural resources,’” Hanson says. Oaxaca’s chocolate, chilies, and an old regional favorite, fried grasshoppers, are popular on many café and restaurant menus… Mesquite flour? Not as much right now.

Food journalist Fred Jimenez has worked out many mesquite recipes for Hanson and Xuchil. Recently, he was a chef at Exhacienda Guadalupe, a retreat center that is also home to the design center Oax-i-fornia, which promotes local artisan crafts. “The flavor intrigues me,” says Jimenez, who’s tested the flour in everything from fettuccine and fried chicken to banana bread and pan de muerto, the bread served during Day of the Dead celebrations. “It’s between sweet and something like the husk of wheat or toasted wheat. I wanted to experiment with that little pinch of sweetness.”

Joseph Gilbert is chef-owner of El Destilado, a contemporary place in Oaxaca’s historic center known for its novel multi-plate chef pairings. Mesquite flour makes the crust of his key lime tartlet more dense and nutty-tasting, and gives an earthy depth to the spread of crumble he serves with homemade ice cream. He’s using Xuchil’s beans in culinary experiments with seasonings made from an edible Japanese mold called Koji. “Mesquite flour lends a depth of smokiness and sweetness,” he says, “similar to the effects the wood has when using it to smoke food products.”

Hanson and Garcia also test the flour at their Oaxaca home. “We’re making a sweet extract that is used in many ways – in ice cream, in butter, in mixed drinks,” Hanson says. “There’s a byproduct I toast and mill in a coffee grinder.” He brews it with hot water and drinks it every morning. “It tastes like caramel coffee.”

To refine their production, Hanson has connected the Xuchil team with engineering students at the University of Texas, Austin, who design and test equipment prototypes in their classrooms, then visit the Etla Valley during spring break to help build final systems. Last year they constructed a greenhouse outfitted with mobile racks. The cooperative also built rinsing and drying stations on the rooftop of its headquarters, taking advantage of the intense solar power concentrated there.

“The earlier dryers were efficient, but we just had a very low capacity,” Cruz says. “We could dry a maximum of 24 kilos or so of beans in two days. With this new greenhouse system, we can dry up to 120 kilos in the same period. The drying process itself is fundamental in our production.”

The word collaboration comes up a lot at Xuchil headquarters. “One thing that’s really important to this project is the social part, the idea of spending time with another human being,” says Xuchil’s Antonio Garcia Lopez. “Like with the harvesters — we eat with them, we spend time with them. They like how we’re collaborating with them, and we see that our purchases of beans from them are definitely increasing the incomes for families.”

Above. Xuchil Natural Foods in Mexico’s Etla Valley mills high-protein flour out of mesquite beans from a historically significant agriculture valley three hours’ drive away. Oaxacan chefs develop recipes for bread, desserts, and pastries using mesquite flour made by Xuchil. Minerva Cruz Vasquez leads Xuchil, whose entrepreneurs studied in a local business program to market goods made from existing resources. Here, she scans the fertile Etla Valley from a rooftop greenhouse built for drying mesquite beans.

Tree mystique. Back in the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Valley, residents are not surprised that their mesquite trees have lots of value. They’ve known that bit of wisdom all along.

“We use the resin as a natural glue when we make piñatas,” explains Javier Ortiz Bautiste, who owns Tio Jose’s restaurant. “You can also use the resin for medicinal purposes. If you hurt yourself, if you break a bone, or you have some kind of injury in your arm or leg, you can apply the resin. It reduces the pain.” A tincture made from the leaves can soothe sore eyes, and the sap that Cruz and Hanson found so bitter is a self-generated salve the tree uses to heal its own wounds.

For the eight or so women Xuchil employs as harvesters, the local trees are an economic windfall. The work adds an extra $40 to $80 a season to incomes that are tied to the farming of crops like papayas, melons, and the fruit tree chicozapote.

As Cruz, Hanson, Olivares and the rest of the group exit the mesquite woodland after their harvesting excursion, Ortiz and Olivares point to how easily tender young trees are already sprouting.

Later at her home, Olivares serves up hunks of fresh bananas to the hungry crew. The $4 U.S. per 15 kilo bag she’ll make from Xuchil this year will help her to buy beans, corn, and medicines for the household. She smiles at that.

Saving Italy's Mountain Villages - Rhapsody magazine

IF DANIELE KIHLGREN had his way, the Italy you experience as a visitor would not be manicured Tuscany or spit-shined Amalfi Coast but the stone-cool inside of a medieval room in a village called Santo Stefano di Sessanio, its mattresses thick with local wool, its fabrics spun by artisans living nearby. Cobblestones and floorboards would be scalloped by a million heels, and windows would open onto landscapes marked by farms from the Middle Ages.

Preserving the features that make a place unique is the mission of Kihlgren’s pair of boutique lodgings (one here and one in Matera), both called Sextantio, the early Roman name for the village where he developed his first hotel. The Swedish-Italian entrepreneur is using tourism to save Southern Italy’s hilltop towns, which are facing extinction after years of emigration.

“Today, we are living in worlds that are losing their identities,” Kihlgren says. “One of the big losses in Italy after the post–World War II economic boom of the 1950s and ’60s is that too many historical places have been replaced by ugly cement housing.” In an ironic twist, Kihlgren’s family fortune came from the same cement industry that built these boxy, anonymous postwar suburbs. “People,” he says, “are nostalgic for the old Italy.”

KIHLGREN FIRST SAW the pretty crenelated tower in Santo Stefano di Sessanio, an Apennine town in the province of L’Aquila, in 1999, while motorcycling through the humpback mountains of Gran Sasso National Park. He bought up as many properties in the nearly abandoned village as he could and, in 2005, opened Sextantio Albergo Diffuso—or “scattered hotel,” a reference to the way rooms are peppered throughout the village.

Guests enter a lobby in the town’s former stables at the top of the hill and are escorted through narrow lanes to their dwellings. Kihlgren installed modern technology and earthquake stabilization but preserved original walls and floorboards; chairs might have belonged to work-worn shepherds or members of the famed Medici clan, who once ruled this region. The hotelier even tapped an anthropologist to recreate old formulas for soaps, shampoos, and candles, using such ingredients as lupine seed and flax. In an on-site artisan workshop, guests can learn how to craft straw chairs and tables, make natural oil soaps, or weave scarves, hats, and wraps.

“When people make a new hotel, they renovate away the cultural identity,” he says. “In a way, they obscure the emotion of such places. Sometimes people don’t understand that old places have an emotional impact. In a place like this, you change your pace, you become more calm, less neurotic, less obsessive. You are in tune with what you have around you.”

In 2009, he opened a sister property in the UNESCO-designated district of Sassi di Matera, in the Basilicata region (roughly the “instep” of the Italian boot), where people have lived in caves for some 9,000 years—making it among the oldest continuously inhabited settlements in the world. Rooms at the Sextantio Le Grotte della Civita are illuminated with beeswax candles and beams of sunlight entering through slots carved by prehistoric troglodytes. Sinks are built into mangers once used by donkeys, but there are still a few nods to modern luxury, including bathtubs by Philippe Starck.

MATERA WILL BE CELEBRATED as a European Capital of Culture in 2019, and in preparation Kihlgren is transforming 14 more abandoned caves at Le Grotte della Civita into hotel rooms, a restaurant, and a new spa. Kihlgren says the spa’s approach will be “linked to Matera’s system of cisterns and underground water collection,” while treatments will incorporate herbs foraged from nearby Murgia National Park.

Perhaps no amenity at the Sextantio Albergo Diffuso better expresses Kihlgren’s philosophy than the carafe of homemade genziana—a liquor infused with the roots of yellow flowering gentians—that he leaves out for guests in the hallways. One sip communicates everything he wants you to know: With no sugar added to soften the shock, the true-to-life spirit splashes the tongue with gusto.

“It is bitter,” Kihlgren says. “It’s expressive. I like that.”

World's Toughest Musher, DeeDee Jonrowe - Homestead Magazine

ON THE MORNING of Aug. 1, 2013, Iditarod legend DeeDee Jonrowe peeked into a wooden doghouse fenced off among some trees on her property in Willow, Alaska. Inside was Challon, a husky that Jonrowe had recently bred to an athletic male dog named Jarvi. Nearby, tethered to their own houses, more than three dozen other dogs made a symphony of howls.

A day earlier, Challon had nudged away her kibble, exhibiting a classic sign that she was ready to release her pups. By the time Jonrowe reached the pen, five pups had squiggled out of the womb and onto the hay beside their mother.

Five was a fine litter size, but Challon wasn’t done. Another body emerged, and then another, until finally the puppies totaled nine. This was already no ordinary group.

“It’s going to be my next race team,” Jonrowe said, her voice sparkling.

Five foot three, sixty years old, and a bundle of muscle, Jonrowe is one of the toughest female athletes in the world. She’s not an Olympian or part of any celebrated sports team. Instead, she’s among an elite group of competitors in one of the world’s most grueling races, one that requires marvelous stamina and cunning, and perhaps a little madness: the Iditarod, a sled dog race run every March across 1,000 miles of Alaska’s frozen interior from Anchorage to Nome.

If some people in the mainstream don’t recognize Jonrowe, millions of Iditarod fans do. In 31 races, she’s had 16 top ten finishes and placed second twice. Her pink logo wear is a staple in Iditarod gift shops. Fans know her bright voice from media interviews. “Was that DeeDee?” a hiker asked one day after watching Jonrowe and her two yellow labs charge up the Butte Trail in the Mat-Su Valley. “Tell her that I love her!”

They love her not only for her charm and verve, but also for the way she’s endured some difficult battles.

The Iditarod has a ceremonial start in Anchorage, where fans packsidelines and “Iditariders” (who win at auction with a $7,500 starting bid) ride for 11 miles on mushers’ sleds. The official start is the next afternoon 70-miles north in Willow.

After traversing snow-covered mountains, riveting gorges, and sections of crunched up sea ice, it finishes on the Seward Peninsula in the town of Nome. It links villages of Alaska’s interior that just a few generations ago saw few if any motor vehicles at all during winter. Back then, dogs were critical to survival. Residents raised them for transportation and hunting. Mushers were local heroes, driving dog teams through winter landscapes to deliver medicines, mail, and even preachers. The Iditarod was established in 1973 to honor that tradition.

Only a few Iditarod mushers have become legendary, and Jonrowe is one of them.

Challon is the key.

A mantra among mushers is that the real race athletes are the animals. “It’s not about the mushers,” they say. “It’s about the dogs.”

The sled dogs are fed with meat and fish plus high-calorie, high protein kibble containing amino acids, probiotics and minerals. On the Iditarod trail, the dogs can run up to 100 miles a day, burning 7,000calories per day. They can eat 2,400 pounds of food, all of it dragged in bags and fed to them by the musher. They are rested and inspected by veterinarians at mandatory checkpoints every 18 to 85 miles.

To build a winning team, mushers breed their dogs to have competitive traits, including endurance, speed, a smooth gait, an insulating but not-too-heavy coat, and tough paws. Some, like Jonrowe’s dogs Fudge and Omnistar, become ultra-intelligent team leaders. Others are middle-of-the-pack pullers. Others, still, are wheel dogs running closest to the sled, which can carry more than 100 pounds of gear. Gouda is a favorite wheel dog. In a race, “she’s directing my sled,” Jonrowe explained. “She plays the back line like a piano wire. She’ll jump over, and have both dogs pulling the sled away from the obstacles.”

The performance qualities come only with practice, training and good health. Managing that is much more than a full-time job; it’s a lifestyle.

Touring Jonrowe’s 17 acre property, it’s clear the yard is planned for efficiency: tethers keep dogs from tangling with each other; wide corridors allow for poop cleanup and snow shoveling; and the houses, made by Jonrowe’s husband, Mike, slide up and down on poles so they can be raised and lowered with the snow level.

“Any one year we might win or we might have a bad year,” she said, “but we’re taking care of the dogs 365 days a year. We’re living with them and their little idiosyncrasies. We’re providing for them.”

The bonds that develop between dog and musher make all the difference in the race. The team tries to navigate and avoid many disasters on the trail, from tipping over the sled to getting a dehydrating flu that can spread among participants. One particular day remains strong in Jonrowe’s memory, and marked a turning point for her. Near the end of the 2002 race, crossing the sea ice to the town of Golovin, she felt strangely weak.

“Walking the dogs across the bay, I was stumbling and falling,” she said. “The dogs would come along up around me. I was sure I was going to die out there that night.” At the check point in Golovin, she drank several liters of fluid to stem her dehydration.

A few months later, she learned she had breast cancer, a disease her mother, Peg Stout, had beaten a few years earlier. But cancer couldn’t chase the Iditarod out of her. The next year, three weeks after finishing chemotherapy, she raced to Nome in 18th place.

And that’s where the second key to Jonrowe’s success comes into play: an ability to focus and recover even when things get impossibly bad.

On the Iditarod, quitting the race because you’re tired is not an option. “Somebody has to risk their life to come get you if you quit,” Jonrowe said. “To just quit takes an extreme situation.”

In 1999, she had that extreme, and it was threatening her dogs. “I had bad storms and leadership issues,” she said. “I was 90 miles either direction from anything. I couldn’t walk in front of the dogs to take them in safely anywhere. I made camp for them, and the storm raged and raged.”

Eventually, she signaled for rescue from a bush pilot. “That was one of my lowest points in racing,” she said. “I took all those dogs safely off the river, and two years later we made a top ten finish. We regained their confidence and mine. Sometimes the steepest learning curve is in failure.”

But her most persistent stronghold is in her spiritual faith.

“I like the adrenaline of the edge,” she explained. “People talk about faith being a crutch, but faith is my parachute. I can jump off the edge because I’ve got faith. Whether that’s a good idea or not,” she laughed, “that’s how I live my life, and it’s worked real well.”

Jonrowe’s kitchen is a few steps from the yard where her top competitors live. Someday some of Challon’s pups might be there, too. Like she does most early mornings, the musher watched the dogs through a window, observing them closely for injury as they stretched and took their waking steps.

“Our concept is to know our dogs well,” she said. “All year I’m learning about their potentials, their comfort zones and their talents.”

When feeding time arrived, some of the keenest four-legged athletes in the world howled, leaping up on hind legs in order to touch their keeper.

Jonrowe called out to them brightly. “Good morning, Merlot! Hello Gouda!”

After the dogs chewed and drank, they settled down with eyes closed. “Look at them,” Jonrowe said. “They’re so happy, happy, happy. As (Iditarod champion) Martin Buser says, when you provide for everything they need, they’re content. They’re saying ‘We’re warm, we’re fed, we’re watered….’”

“But then,” she added, “a sound might wake them, and they perk up. They say, ‘There might something happening! There might be something…’.”

All Photos Copyright Laura Read

Shake, Rattle & Roar — Moonshine Ink

By Laura Read

THE RECENT QUAKES AROUND LAKE TAHOE have not only jiggled residents’ homes, they’ve also unleashed thoughts of the “Big One.” The fears are not unfounded, scientists say; but a prediction is elusive, and there’s still a lot to learn. One thing we know is that the story begins deep in the past.

Between 12,000 and 21,000 years ago, a strong earthquake shook Lake Tahoe and loosened about 3.5 cubic miles of earth on the West Shore around McKinney Bay. The debris tumbled downward and across the lake bottom with such force that chunks scattered as far as 9 miles out. Slabs a mile across and 500 feet high stayed intact, according to recent measurements. The McKinney Bay Landslide cut a chunk out of Lake Tahoe’s shoreline and gave it the west-bulging shape it has today.

But the drama wasn’t over. The cascading earth sent a giant wave surging eastward in a swell that reached 330 feet high. The action is animated in a 15-minute film produced by scientists at the UC Davis Tahoe Environmental Research Center (TERC), called Tahoe In Depth 2D. Images generated by sonar and radar equipment reveal just how much impact the tsunami probably had.

Advertisement

The powerful wave offset by the crumbling earth moved so quickly it took less than 10 minutes to cross the lake and roar up canyons on the East, North, and South shores. In 10 more minutes, the water receded from those hillsides, then splashed up on all sides of the lake. Sloshing back and forth, then, like water in a tilted tub, it scoured the slopes and pulled every living and loose thing downhill. According to geologists, Eagle Rock, a volcanic plug at the mouth of Blackwood Canyon, received a sort of neck scrubbing; its base shows the evidence to anyone looking closely today. The new lake bottom was now scattered with monolithic rocks and deposits of sand and gravel from the mountainsides. Today, the subaqueous wonderland is a fascinating place for scientists to explore, which they do using submersible diving vehicles, remote-operated vehicles, and underwater photography.

It’s not crystal clear what caused the McKinney Bay Landslide, but scientists like Richard Schweickert, emeritus professor of geology at the University of Nevada, Reno, say it probably was a profound quake. Sediments on that side of the lake contain weaker layers of an ancestral lake, Schweickert said. They did not hold up to the earth-ripping jolt.

Despite the dramatic past, tsunamis haven’t been top of mind for many geologists; but this spring, on the morning of May 28, one of Lake Tahoe’s three faults, the Stateline-North Tahoe Fault, shifted twice, 30 minutes apart, at magnitudes 4.2 and 3.1. Not only the scientists paid attention. Other observers wondered, “Are we in for The Big One?”

Alert!

“It’s a wakeup call,” said Jim Howle, with the U.S. Geological Survey. “This is a good time to think about earthquake preparedness.”

Tension and Release

In fact, Lake Tahoe is due for a major rupture. If it occurs, it will most likely be along a 25-mile-long crack that lies west of the Stateline-North Tahoe Fault Zone, called the West Tahoe-Dollar Point Fault Zone, scientists said. Whether that happens tomorrow or in a thousand years is anybody’s guess. “Take a yard stick and bend it, and tell me when it’s going to break. If you do it gradually, it won’t break; then, boom, it breaks,” said Graham Kent, director of the Nevada Seismological Laboratory at UNR. “Sometime in the next thousand years — or maybe tomorrow — we’re going to get that West Tahoe Fault going, and it will be a catastrophic event.”

The idea that precursor quakes, or foreshocks, will warn of such a catastrophe is a misnomer, Howle said: Sometimes earthquakes have foreshocks and sometimes they don’t. “There’s no such thing as an early warning system for earthquakes,” he explained. That said, there have been thousands of little quakes in the Lake Tahoe Basin and surrounding areas that have not drawn much scrutiny, but the bigger quakes of May 28 caught his attention. “This is about as close as we get,” he said.

One place the public has turned to for information is TERC. The research center does not have a geologist on staff, said Heather Segale, TERC’s education and outreach director, but its focus on the watershed and lake health intersects with geological research. After the quakes, more than 100,000 people tuned in to the center’s YouTube channel to see Tahoe In Depth 2D, Segale said. “The earthquakes definitely have people interested in learning more.”

Heat, Ice, and Water

It’s easy to admire the lake’s sublime beauty, and to be comforted by the fact that in recent centuries, the features haven’t changed much. But geologists — who think in much broader timespans, in millions and millions of years — know that all of the earth’s surface is constantly rising and falling as the tectonic plates that form it shift under gravity’s pull.

As these tectonic plates push against each other, tension builds, Howle explained. The pressure or energy must be released, and is usually let go in a tremor, or quake, which can cause a rift in the earth called a fault. Ruptures can appear as “normal,” or “step,” faults, which slide vertically against each other and make a cliff drop pattern; or they can take the form of a “strike-slip” fault, which shifts from side-to-side the way two palms rub together, fingers to thumb.

Even though Lake Tahoe is huge and seems like its own entity, it is nevertheless part of the much larger region extending eastward into Nevada and westward all the way to the Pacific Ocean. Two million years ago, the Basin was less dramatic and held a shallow lake that captured rain and snowmelt, according to Frances Wahl Pierce, a retired geologist and TERC docent who hosted a video about the lake’s geology for TERC’s YouTube channel. Over time, as the Sierra Nevada lifted and a “basin and range” landscape began to form to the east, faults evolved around Lake Tahoe. As the faulting grew, the Tahoe Basin got deeper — even more so than today, for a while — holding a great volume of rainfall and snowmelt.

Volcanic flows on the North Shore blocked the Basin’s sole outlet, now called the Truckee River, Wahl Pierce said. The natural dams contained the water and raised the lake level, but then water eroded them and the lake level dropped, leaving evidence of higher shores on the mountainsides, she said.

Mountain to Basin

The shifting and shaking is far from over. Nowadays, geologists are watching three major normal or step faults that trend north-south through Lake Tahoe, Kent explained. These branch into a combination of normal and strike-slip faults. The West Tahoe-Dollar Point Fault Zone starts at the mouth of Emerald Bay and trends north along the West Shore to the east side of Dollar Point and beyond toward Northstar California Resort. Its effects can be seen from the Rubicon Trail at D.L. Bliss State Park, where a cliff plunges into deep blue water that’s 1,400 feet deep, and divers find boulders and fissures to explore. It also appears along Dollar Point, where, within 20 strokes, kayakers can cruise from water that’s 10 feet deep and the color of turquoise to water 30 times the depth and darkened to a haunting indigo hue.

East of the West Tahoe Fault, the Stateline-North Tahoe Fault Zone runs from Stateline into the lake at a southwest angle. It forms a steep drop just to the east of Cal Neva in Crystal Bay, plunging to the deepest part of the lake, 1,644 feet. Paralleling this is the Incline Village Fault Zone, Kent said. It runs southwest into the water out of Incline Village, cutting through land less than 2 miles away from the Tahoe Environmental Research Center.

Relatively recent breaks, the result of fault zone activity, are visible above ground in a couple of places, Kent said — near the old elementary school in Incline Village and at the Angora Lakes trailhead south of Fallen Leaf Lake.

It’s not easy for even scientists to tell exactly where a quake occurs. An earthquake’s epicenter is determined in part by its distance underground, as fault ruptures exist at specific depths, Schweickert said. When they run close to each other, as is the case with sections of the West Tahoe-Dollar Point and Stateline-North Tahoe faults, quake location will be determined by which depth the tremor corresponds to. Best indication so far for the May 28 quakes, according to Kent, is the bigger rupture was “a relay fault zone between West Tahoe Fault and Stateline-North Tahoe Fault — and was strike slip, left lateral,” meaning the epicenter occurred on one of the rifts that branch off the main artery of the fault trending from the north middle section of the lake through Stateline.

Action Everywhere

The Tahoe-area faults do not stand alone. They belong to an extended series of rifts that trends both south and west. Named Walker Lane, this zone is connected to the San Andreas Fault along the Pacific Coast, said Annie Kell, previously an education and outreach seismologist at UNR, in a video lecture for TERC citizen scientists preparing to paddle the Lake Tahoe Water Trail last month. The San Andreas Fault gets about 75% of the overall region’s activity, while Walker Lane exhibits 25%, Kell said. Walker Lane has experienced thousands of jolts across the centuries, from Mina, Nevada, to Mammoth, California, to Independence Lake. From mid-May to mid-June this year, the Stateline-North Tahoe Fault Zone alone ruptured dozens and dozens of times, according to USGS online records.

Kent has a creative interpretation of how the combined movements shaped Lake Tahoe. If you hypothetically combine all of Lake Tahoe’s known previous jolts in one long segment, the time it took to form the lake would comprise just half a day. “Lake Tahoe was formed in six hours of actual hell and terror separated by thousands of years,” he said. “There is mostly quiescence and then there’s a bad 30 seconds.”

Kent has studied the earthquakes recorded along the Pacific Coast and inland: He sees the big picture and finds it alarming: “Lake Tahoe could be the most dangerous geological hazard in the lower 48,” he said.

One reason is that thousands of people are present in the Tahoe Basin on any given day, he said. They’re sunbathing, dining in cafés, playing with dogs, skiing its slopes, or driving to work. Another reason is: At least one primary fault is overdue to rupture in a big way.

When geologists say the West Tahoe-Dollar Point Fault is ready for “the Big One,” they’re assessing risk by timeframe. It’s been 4,500 years since the last large rupture along that line, according to Kent. The known major event before that was 7,800 years ago, he said. The one prior to that was 11,000 years ago. If the time between significant ruptures is a pattern — roughly 3,200-year intervals — then the West Tahoe-Dollar Point Fault could be in for a big quake soon. Normal, or stepped, faults like this tend to rupture in large singular events, Kent said.

Tsunami Watch

That major earthquake could be bad enough, but will it also trigger a tsunami? Kent and other geologists interviewed said that kind of event is hard to predict. “It is a fact, you will generate a tsunami of a certain size by just dropping the Basin floor,” Kent said. A tsunami could also be triggered by a landslide that might come from a rupture in either a normal fault or a slip-strike fault. “The height is dependent on how that rupture happens,” he said. How will it affect people? “It depends on where you are around the lake and how unlucky you are on the shoreline.”

When asked how worried he is that a tsunami will occur soon, Kent said: “I work with fire departments. I’m worrying about Tahoe burning down about 10 to 20 times before we have an earthquake.” On the other hand, he also advises, “If there’s strong shaking at the beach, get off the beach immediately. If you see big changes in water level, get off the beach …. To a degree, we know we are running out of time on the West Tahoe Fault. It does have to relieve its stress.”

Kell — and Howle, too — won’t avoid Lake Tahoe. But they are wary. “It’s a good reminder that bigger earthquakes are not out of the question in this area, and everybody should take heed,” Howle said.

The Seaweed Forager, Dingle, Ireland - The Furrow

SOME 10,000 KNOWN SEAWEED varieties grow in oceans worldwide. Six hundred of those live along Ireland’s 3,000-mile-long coast. On the Dingle Peninsula in County Kerry, Darach Ó Murchú keeps track of his local species using notes that are hand written in minuscule print on water-proofed paper. He understands something that many land-dwellers don’t: Among pools left behind by the receding tide exists a magnificent world of edible plants.

“Some resemble trees, others resemble miniature plants, and others look like grasses,” Ó Murchú says. “They have all sorts of different forms – spirals, snake-like, sausage-shaped, tuber-shaped. Some are microscopic; others much deeper are massive, growing 150-feet tall.” He knows this world more intimately than most, and he wants the people who aren’t as well acquainted with oceans to know it, too.

Ó Murchú is reaching out by teaching about seaweeds in class offered through his business, Elements Outdoor Training, and as part of seaweed foraging and cooking classes at the Dingle Cookery School. Spending a few hours on the seashore with students, he explains how to identify, find and harvest up to 10 different kinds of seaweed. The group then travels a few miles away to Dingle, the peninsula's main harbor town, where they learn from Ó Murchú and Chef Mark Murphy how to use the seaweed they’ve collected to enhance their food. The course fits well into the Dingle Cookery School curriculum, which showcases fresh-caught seafood and traditional Irish cuisine.

“There’s been a great interest in seaweed in recent times,” Murphy says. “Darach has spent many years learning and using different seaweeds. He is a natural teacher.”

CHEWING SEAWEED IS TOUGH. It can be overwhelmingly salty, and smell unpleasantly fishy. And yet, people around the world are getting excited about its culinary possibilities. Some say different varieties can do everything from fight infection and rejuvenate adrenal glands to quell inflammation. It can boost calcium, magnesium, iron, potassium, manganese, and Vitamin B12, according to experts. It can nourish the skin and ease congestion. For cooks, when seaweed is prepared just right, it’s also good to eat.

“These are the first two seaweeds I came in touch with as a kid,” he says. “The dillisk — I loved because it’s a salty, chewy snack. The carrageen, I didn’t love. My mom used to make ice cream with it. It was absolutely disgusting. There would be war in our house when she made it. Now I like it, of course.”

HIS WAY OF LOOKING at things comes from the unusual life he’s led life so far. He studied engineering at the Dublin Institute of Technology and then worked in Silicon Valley. He studied to be a mountain guide in Scotland, and led expeditions to the Himalaya and other high places. He’s always returned to the Dingle Peninsula, where he spent a lot of time as a child. Now, in between other stints, he teaches people that the sea plants they’ve thought to be stinky and ugly – are actually worth a taste.

The foraging workshop begins with a simple lesson: There are three classifications of seaweed — brown, red, and green. Even this little spot, the size of a small back yard, is diverse. There are groups of bladder wrack, oarweed, and dillisk – “powerhouses against cancer,” he says. And there are patches of carrageen and tangles of sea spaghetti.

Using scissors, Ó Murchú removes a strand of shiny, strappy oarweed (a type of kelp), leaving roots intact so the plant will grow back. “The Japanese use a closely related seaweed called Kombu to make dashi soup stock,” he explains. He runs his fingers along the side, drawing attention to the glossy gel that adheres there. “It has a strong umami flavor, and will deepen the flavor of anything. I’ll wrap a fish in one of the big fronds and bake it in the oven. The kelp gives it a bit of depth and flavor – a richness and a fullness.”

He cuts a branch of chestnut-colored pepper dulse. It’s also called the “truffle of the sea,” he says. Snipping it into bits, he fans the pieces onto his palm. “I grind this to powder and then sprinkle it on top of food — anything I think it goes well with. It’s tiny, but it’s just … powerful.”

HE LEANS OVER A CLEAR POOL that’s been left behind in the rocks by the receding tide. It’s full of filmy tendrils, brownish soft button shapes, and translucent leaves that seem spun of a lime-green silk — sea lettuce. The small pool illustrates a big concept. “These seaweeds are quite extreme in that they have to put up with extreme conditions,” he says. “On a sunny day, a lot of the water evaporates and leaves the salt behind, and then on a rainy day the rainwater fills the hole and the salt gets diluted or washed out.”

As students peer ever more closely, the discussion meanders, and soon the course is about much more than plants.

Generations ago, Irish farmers were building new soil and enriching existing soil by folding in strands of seaweed they hauled from the shore zones. In certain parts of the island’s west coast, the technique is still in use. Ó Murchú worries that the rocketing world demand will cause careless harvesting and will damage marine ecosystems. He hopes to raise awareness in the class.

HE GENTLY PUSHES his thumb at a thimble-sized anemone to demonstrate the way it forces a mild suction against the skin. He points to cone-shaped limpets that look like volcanoes in a world of miniature Lilliputians. “That’s their patch for the rest of its lives,” he explains. Their calcium shells are developed to connect with the rock contours where they were formed. “Once the tide comes in, they’ll be eating small seaweeds on the rock or elsewhere. They have a tiny foot, and they’ll leave this spot and wander around.” The limpets wouldn’t be able to get the same seal against a rock if they were to settle in another location. “Once they sense the tide is going out, they come back to the same place,” he says.

When he’s foraging, Ó Murchú, too, watches the rise of the sea. Absorbed in the work of inspecting this freshly revealed ocean world, he can be surprised to find that so much time has passed, and the tide is returning.

Amid Record Snowfall, A Tragedy - Front Page, San Francisco Chronicle

The morning of Jan. 24, at Squaw Valley Ski Resort was one of the most spectacular in recent memory. After years of drought, three storms in a row had blanketed Squaw’s legendary slopes with a dry, crystalline powder, the stuff of skiers’ dreams. Along with the rest of Squaw's ski patrollers, 42-year-old Joe Zuiches prepared dozens of hand charges – cap-and-fuse initiated explosives — and traveled by snowcat or chairlift up into the mountain’s most rugged terrain.

Normally, patrollers and other employees opening the mountain work a delicate dance of movement and communication to trigger avalanches in unstable terrain. The snow must be blasted from places where it builds up during storms from wind and snowfall and becomes unstable enough to topple onto ski runs. That can happen with a loud sound, a blast of wind, the movement of a skier, or the changing weight of the snowpack as the sun warms and binds the top layers. This day, something went terribly wrong.

By 8:35 a.m., Zuiches stood on a planned blasting route along Gold Coast Ridge, peaks of the snowbound Sierra Crest spreading north and south around him. The 42-year-old was killed when one of the hand chargers exploded before he could toss it at its target. He left behind a wife and an infant child, as well as shocked and grieving peers. The incident set off an explosion investigation, still ongoing, involving the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, the FBI, and Cal/OSHA.

“Joe was a beloved leader in our ski patrol, one who served as a great mentor for his team, and we will never forget his dedication to his fellow patrollers and to the safety of our guests, said Andy Wirth, president and CEO of Squaw Valley Ski Holdings. A professional mountain guide and mountaineer, Zuiches climbed Mt. Rainer, Mt. Hood, Mt. Baker, and Villarrica volcano in Chile, and summited Mount Shasta 50 times. He’d been involved in ski patrol at Squaw and earlier at Winter Park Resort in Colorado for 17 years.

Death by an exploding hand charge has occurred twice previously since 1973, when a Mammoth Mountain patroller was killed, according to snow and ski safety consultant Larry Heywood //OF WHERE?//. There are strict protocols and many guidelines to ensure safe use of explosives at resorts, but on this, one of the most anticipated powder days in years, the hand charge claimed its third victim.

Using hand charges in resort avalanche mitigation is a common practice around the world, according to Geraldine Link, director of public policy at the National Ski Areas Association. The blasting creates a controlled slide before it can become a hazard. In addition to the hand charges, resort patrollers control unstable snow with projected explosives from mounted military artillery and avalaunchers (air-powered cannons). They also release snow by skiing patterns across areas of unstable buildup, a practice called ski cutting.

Hand charges are used to trigger snow in areas that the avalaunchers and artillery can’t hit, according to Heywood, who was ski patrol director at Squaw’s neighboring Alpine Meadows Resort for 17 years. “Given squaw’s steep terrain and at times intense snowfall and wind, Squaw has one of the largest and most complex hand charge programs of ski areas in the country,” he said. “There are a lot of small pockets that the other equipment wouldn’t be appropriate for. The artillery can’t hit every nook and cranny. You can get to all of those spots on skis.”

Patrollers travel well-established routes that put them into position, usually above a targeted slope, said Heywood. Squaw, the site of 1960s Olympic Games, has 60 full- and part-time professional patrollers who handle thousands of rounds of ammunition per year at the resort.

Recently the resort added to its arsenal five Gazex Inertia Exploders, remotely controlled systems using propane gas and oxygen to create a concussive blast.

Hand charges are shaped as slender cylinders, 2 inches wide and about 12 inches long, and weigh two pounds, Heywood said. They are filled with an ammonium nitrate putty and wrapped in heavy paper. An 18-inch fuse is attached with enough length to allow 90 seconds to pass between ignition and detonation -- a requirement by California’s Division of Occupational Safety and Health.

“Within 10 seconds the charges are supposed to be out of their hands” said Heywood, who helped write the “Avalanche Blasting Resource Guide” for the National Ski Areas Association. “Most of the time you are throwing it downhill, so it can travel a good distance. You’re supposed to then get behind a barrier – sometimes a terrain barrier like a ridgeline – and protect your ears during the blast.”

With the explosion, the hand charge is vaporized, he said.

Patrollers take years of classes, pass tests, apprentice with each other before they become, like Zuiches, a team leader. “Ski areas send patrollers to national avalanche school, and they bring in people to train them at the resort,” Heywood said. “The State of California requires they apprentice for three years under the supervision of a licensed blaster before they can take an avalanche blasting test administered by Cal/OSHA.”

Team members learn about not only the area’s snow behavior and avalanche history, but also how to work in concert with other crews opening the resort. “The job takes a whole lot of people and a lot of focus,” Heywood said.

Link said that safety requirements and avalanche mitigation programs are inseparable. “Unfortunately avalanche work can be dangerous,” she said. “That goes without saying. But three incidents over 43 years — it is just such a rare occurrence.”

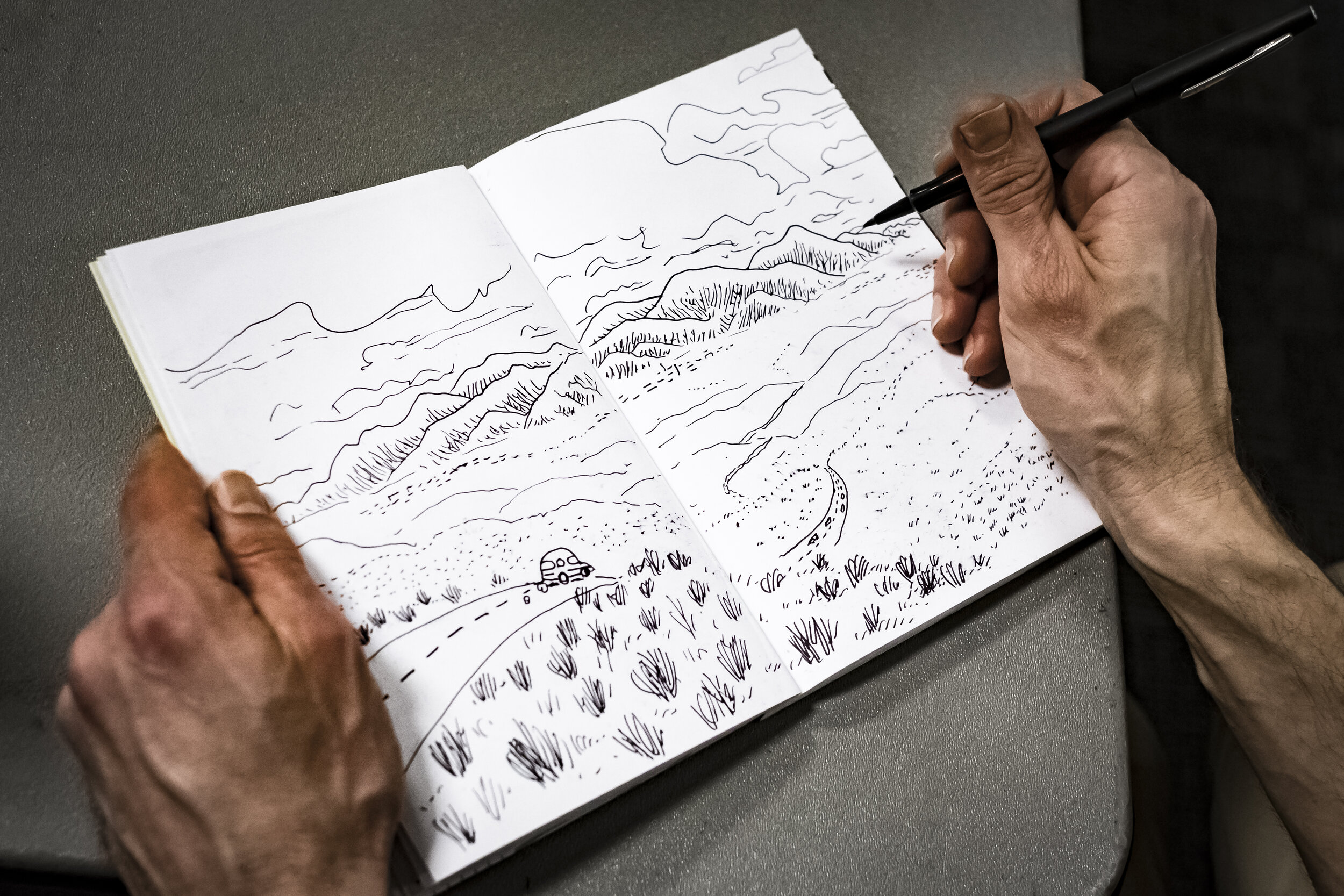

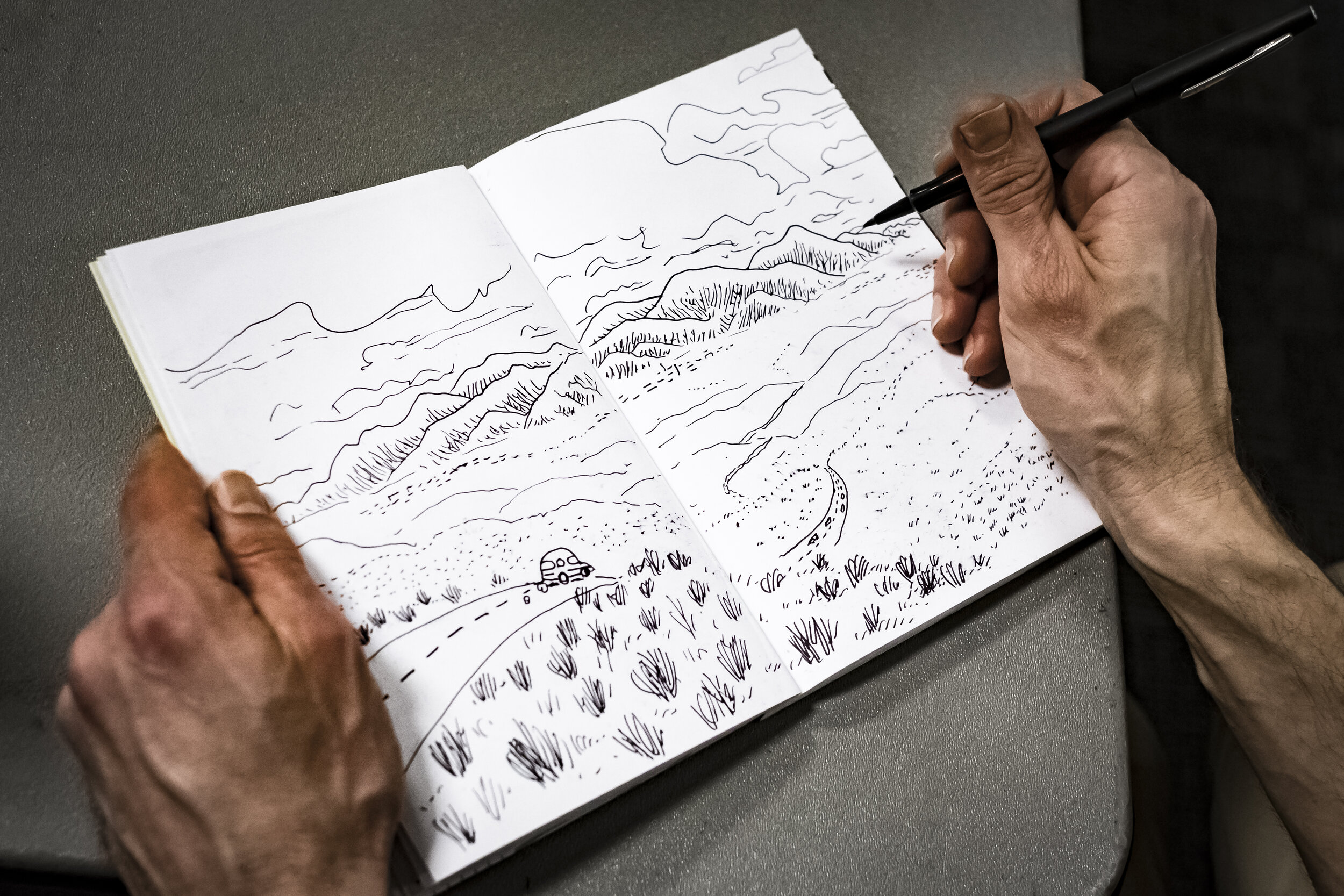

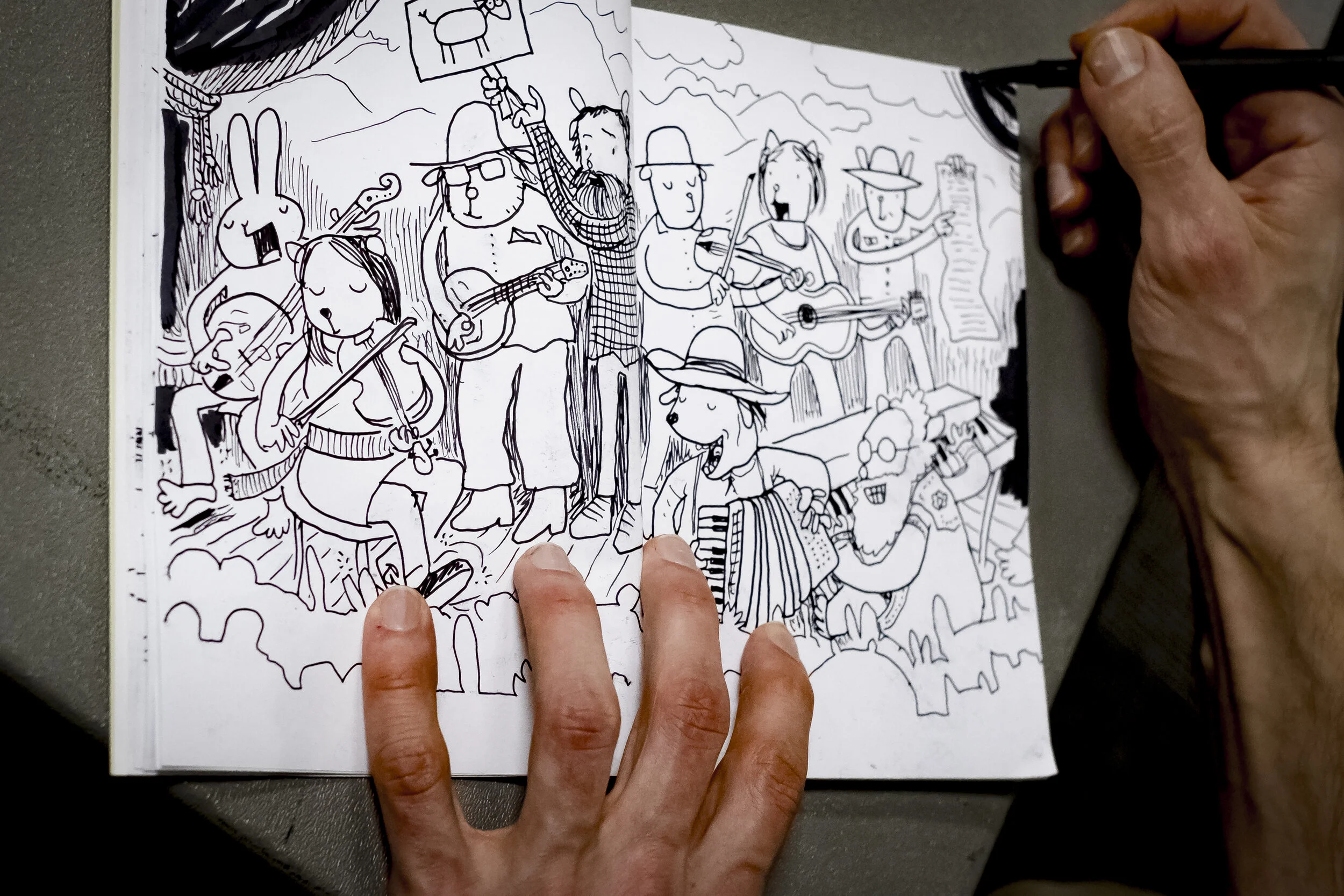

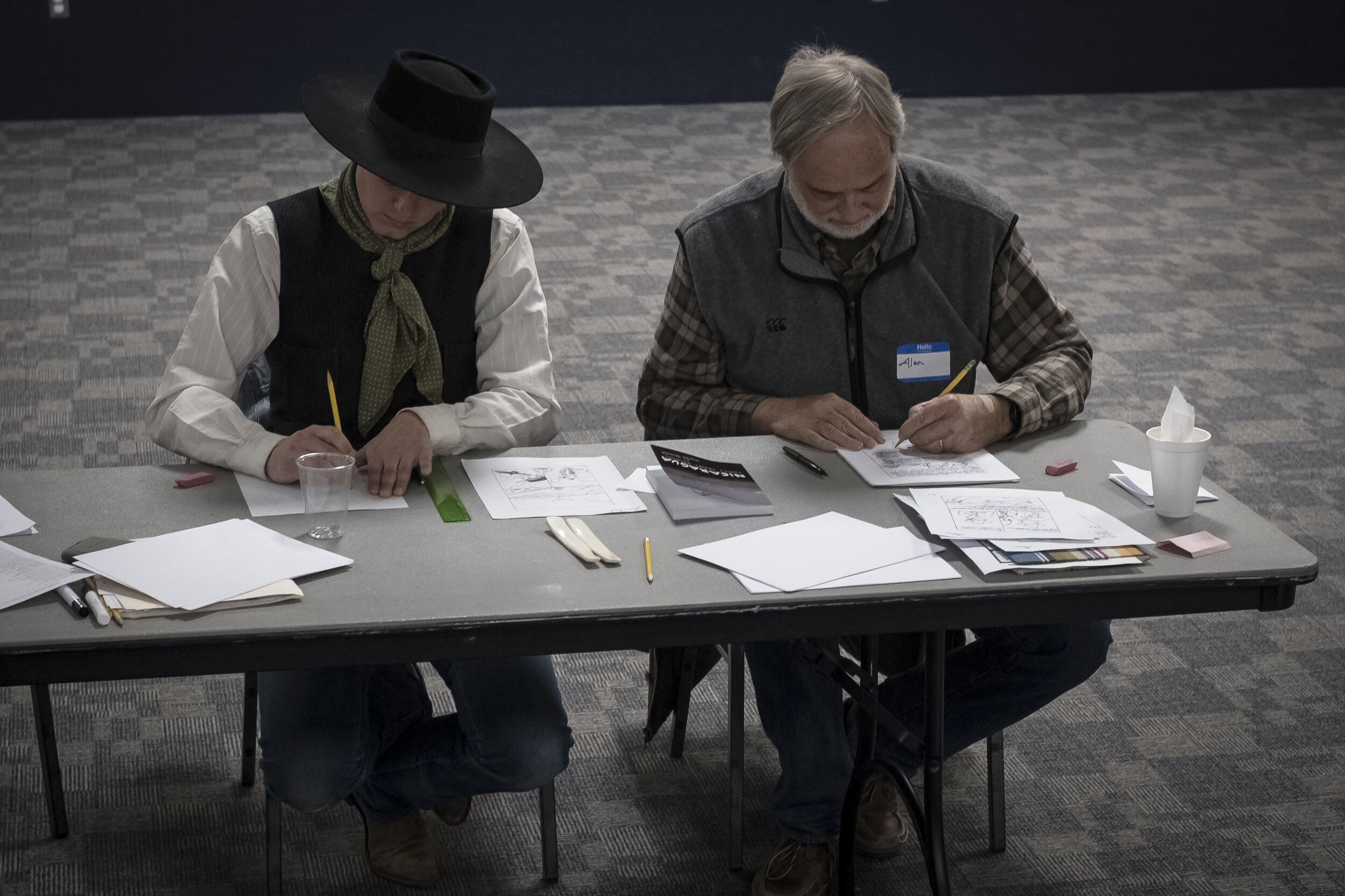

Comics in Cowboy Land - The Furrow

Photos & story by Laura Read

In the first days of the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering in Elko, Nevada last January, graphic novelist Marek Bennett peers excitedly through wire-rimmed spectacles at the adults who’ve clustered in the convention center to learn cowboy comics. The group includes two retired octogenarian ranchers, a couple of practicing ranch owners, and a 20-something buckaroo. There are also city folk from places like Las Vegas, Reno, and Chicago — an investment banker, an insurance broker, a communications specialist, and a member of the media. These are the usual suspects who land in Elko every winter for the week-long celebration of western music, arts, and dance.

The person who is less than usual is Bennett.

A New England native from New Hampshire, the wiry cartoonist wears khakis, converse tennis shoes, and a wool driving cap turned backward — duds that are far from the Gathering’s more common attire of boots, jeans, and cowboy hats. Having a curly beard that sweeps toward his clavicle, he looks like a youngish Abe Lincoln clad in hipster’s clothing.

Bennett and his students represent simultaneous moments in American history that rocked the country into a new age: Folks attending the Gathering admire the Wild West as it was during the decades when 19th century dreamers, wranglers, and shysters spilled out of Midwestern farmlands to settle its unforgiving ranges: Bennett values stories of heartbreak, valor, and change that emerged during the 1860s Civil War.

The two have a parallel of place, too – albeit one that extends across different centuries. Bennett’s hometown of Henniker was settled in 1761, almost 100 years before Elko had a name. Surrounded by lush, forested lands around the Contoocook River, which flows through the Merrimack River into the Atlantic Ocean, Henniker grew up serving farms taking advantage of fertile soil. Bennett now lives on a road named for his grandparents. (They owned a fruit orchard and dairy and his grandfather served for many years as a town selectman.)

Some 2,500 miles to the west, Elko lies in a haunting terrain of dried-up lakebeds and chunky mountains where inland-flowing streams sink blithely into the desert ground. Elko took root a century after Henniker, in 1869, on the banks of the Humboldt River and astraddle the First Transcontinental Railroad. Elko’s first quasi-permanent structures went up just a few years after American leaders declared the Civil War to be over. With nods to the open range, beef cattle and sheep ranchers moved in.

Cartooning History Bennett has many enthusiasms: He plays an 1856-replica banjo in a band called The Hardtacks; he teaches comics workshops around the country; and he educates young artists in schools on the joys of cartooning. But his central focus is making graphic novels about history.

“A lot of graphic novelists are doing really adventurous historical graphic novels right now,” he tells the Elko students at the start of class. His favorites include the 1980s Pulitzer Prize winning “Maus,” in which cartoonist Art Spiegelman interviews his father about the Holocaust, and characters are drawn as mice, cats, and pigs. Another is a 2003 comic strip biography by Chester Brown called “Louis Riel,” about how a 19th century Canadian schizophrenic and rebel leader of the indigenous-French Metis people opposed actions by the government.

Eight years ago, Bennett found his own fantastic piece of the past to retell. In Henniker’s historical archives, he discovered a forgotten 30-page Civil War memoir written by a then-local schoolteacher, Freeman Colby, who described the months he and other members of the 39th Regiment spent building and tearing down camps, repeating endless military drills, choking down “hardtack” flour-and-water biscuits, recovering in sick rooms, and occasionally fighting their countrymen on the battlefield. Bennett knew that if Colby’s stories were brought to life in a graphic novel, they would relate the Civil War in a fresh way.

“I was really curious about Colby's story, and I realized drawing it out panel by panel would help me to understand it better,” Bennett says. “I also felt an urge to help Colby tell his story to a new generation of readers...possibly his first ever generation of readers. I think that diary's been sitting in a box on a shelf for many, many years.”

Admittedly, the Civil War isn’t the first bit of history to flood minds when people think of comics. This bloodiest of all American conflicts, it scarred America’s early territories from Virginia to New Mexico, involving some 3 million fighters and leaving between 620,000 and 850,000 men dead.

“Colby’s story takes place at a cataclysmic meeting point of two worlds,” Bennett says, “an old agrarian world that had existed for centuries, and a new industrial world still forming. It was a fascinating fault line between the Middle Ages and the Modern World. It was that most distant point in history where I could recognize my own world, my own modern perspectives in some of the stories that come down to us. Here was this young school teacher from my town, writing about his experiences along that fault line, sharing his perspectives with us, if we would only take the time to listen — I mean read — I mean draw!”

In 2016, some 340 pages and thousands of cartoon panels later, Bennett published “The Civil War Diary of Freeman Colby.” Its drawn stories are fascinating, funny, and tragic. Enough excitement bubbled around that book that this winter he launched a successful Kickstarter campaign for Volume 2. The book will be available in May.

Cowboys and Comics In the convention center, Bennett warms up his budding artists with a camp humor rhyme called “Boomer Johnson,” written by Henry Herbert Knibbs about a gunslinger who “quits a punchin’ cattle and takes to punchin’ dough.”

“….He built his doughnuts solid, and it sure would curl your hair

To see him plug a doughnut as he tossed it in the air.

He bored the holes plum center every time his pistol spoke,

Till the can was full of doughnuts and the shack was full of smoke….”

When Bennett explains his drawing process, it’s clear his cartoons don’t pop without a hitch onto the page. He first drew Boomer as a human figure in a broad hat and a dark mustache. Then he stepped back. “I got to looking at my characters and thought, ‘Wait a minute; I have made an assumption about cowboys,’” he says. “I’d drawn the types of cowboys I’d seen in movies. Who knows? Statistically, in reality, maybe they were not all white or even all male.’” He redrew the gunslingin’ pastry chef as a figure less threatening, more abstract — a mustachioed swine wearing a vest and cowboy hat. The picture sends the students into giggles, exactly the response that both Bennett — and Knibbs — had in mind.

Is it a Cowboy Poem? The Cowboy Poetry Gathering draws performers from all over the world — from Jiggs, Nevada to Tulare, California, and from Hungary, Italy, Mexico, and Siberia. For years, one question has ricocheted from room to room: “What is cowboy poetry?” Must it have a full story, complete with beginning, middle, and end; contain line breaks, rhythmic beats, and plenty of white space; conjure scenes of cattle thieves, valiant heroes, evil bankers, lurking coyotes, and lassoing vaqueros? Or should it be free from all that?

In 2017, the Elko nonprofit that organizes the event, the Western Folklife Center, hired a new director, Kristin Windbigler, who is kindling a flame under that very discussion.

“In curating this year's Gathering,” she explains, “we wanted to make room for all sorts of stories that show the incredible variety of experiences, opinions, and beliefs among people who make their livings close to the land, and how much those people care about their communities and roles as stewards of the places where we live. I love old western movies as much as anybody, but that is often the limit of what the rest of the world knows about us. The single story of the rugged individualist, for example, is a stereotype of westerners that is a slim view of history and contributes to misunderstandings of how urban folks see the contemporary rural West.”

Reflecting different interests, the Gathering’s program presents all sorts of western skills, from hat making to leather tooling to Basque cooking. Dance classes include Zydeco, swing, and square. Literary functions address songwriting, journalism, and, of course, poetry. Artistic director Meg Glaser says Bennett’s workshop was the first of its kind here. “We thought it would be fun to give our audience and artists and schools the opportunities to try it out, advance their skills, and see where it goes,” she says. “Cartoons and illustrated letters, envelopes, and poems have long been used by the ranching community as forms of entertainment and expression, but using this medium in a longer narrative comic book or graphic novel form is not so common.”

Comic Strip As Bennett finishes his gunslinger segment, his students put pencil to paper, turning their own stories into dots, lines, and shapes. Their pictures have very clear settings – showing the vast grasslands of Montana, the sagebrush hills of Nevada, the salt flats of Bolivia. They have main characters – a stick-figure horseman, a bulging pregnant cow, a wayward traveling son. They have action – tricking the guys who snipped a barbed-wire fence; forgetting to tighten the horse’s saddle before mounting; rescuing an animal from an icy winter pond. And they have text – “Kersplash!”

Bennett chats while they sketch away. “Even though we're drawing different stories in different styles, there's something at the core that we're all doing – some basic visual human communication that connects and informs and empowers all of us,” he says. “You can see it in ancient cave paintings, in images all through human history, and you feel it whenever you just sit down with friends or family and draw, without worrying about ‘Is it good?’ or ‘Is it art?’ None of that judgmental evaluation matters; it's the moment of communication and recognition that makes all the work worth it.”

When a student asks Bennett what goes in to making his characters appear so frisky and full of life, he suggests the students stoke up their own cartooning spirit by emulating the work of their favorite artists. “It will probably change the way you think of yourself, and your story, too,” he says. “Whatever it is, it has to be something that can't be said by anybody else, in any other medium. That's your contribution to comics.”

The Next One After Bennett’s weeklong immersion in the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering’s western lore, is he tempted to explore in his next graphic novel how a buckaroo swashbuckled his way from a hopeless past to a new community? Perhaps tucked in a drawer deep in the Elko historical society archives, a diary of such a tale is craving to be found. Or maybe the long-lost narrative isn’t that of a cowboy, but of a leather worker opening J.M. Capriola Company, Elko’s famous shop of saddles, bits, and spurs; or of a waitress-turned-boarding house owner who slings hot potatoes, soup, and lamb onto tables for famished sheepherders; or a coming of age story about a ranch kid living in the middle of Nevada’s wide-open basin and range.

As Bennett implies — such stories are for an Elko cartoonist to discover.

The Secret Isle, Ireland's Inis Meáin - Travel + Leisure

Travel + Leisure

THE PLEASURES OF Meáin are simple: a walk along the coast to the thunder of Atlantic swells; a tableau of fissured limestone that glimmers in the mist; the best potatoes you’ll ever taste. At the stone-walled Inis Meáin Restaurant & Suites, owners Marie-Thérèse and Ruairí de Blacam have equipped the five suites with bicycles and fishing rods; oversize beds come with alpaca throws, and 30-foot-wide windows look out onto Galway Bay and Connemara. The real allure is the 30-seat glass-walled restaurant, known for its deceptively basic fish dishes and homegrown vegetables. For dessert, try the seaweed pudding in wild-berry sauce at An Dún.

All Photos Copyright Laura Read

Hiking Across the Stone Age, The Burren, County Clare, Ireland - Sierra Magazine

MY GUIDE IS PETER CURTIN, brewmaster, founder of the Burren Tolkien Society, and owner of the Roadside Tavern in the nearby village of Lisdoonvarna. He is helping me with my mission to visit the various habitats of the Burren, a 220-square-mile rolling limestone massif on Ireland’s west coast. Today we’re going to the top of bare-bones Turlough Hill, where we’ll search for traces of the people who lived here 4,000 years ago.

Under a pale mist, we navigate yawning rock fractures, fields of scree, and stone walls that have stood without mortar for 1,000 years. The Burren is one of Europe’s largest karst, or continuous limestone, regions. The limestone, which formed undersea 320 million years ago, is laced with fissures through which rainwater seeps, to collect in vast tunnel systems. Ferns, mosses, and wildflowers dwell in the cracks. In places, the limestone has eroded to a calcium-rich soil that nourishes meadows bursting with tiny flowers and thick grasses and more than 700 other plant species. Hundreds of generations of farmers have grazed livestock on the meadows. The Irish government now recognizes local farmers as “Keepers of the Burren” and pays them to preserve the habitat.

Atop Turlough Hill we easily locate the ruins: the remains of a cluster of hut sites inside a large circular barricade of stone. Around us, the slinky mist is replaced by a silvery light mirrored in stone. Fields explode in brilliant green, gray hills roll to a bone-white shoreline, and the Atlantic spreads out in a blue sheet.

Curtin believes that the Burren inspired places in J. R. R. Tolkien’s fictitious Middle-earth. In The Fellowship of the Ring, Gandalf says, “The grey rain-curtain of this world rolls back, and all turns to silver glass, and then you see it….White shores, and beyond, a far green country under a swift sunrise.” That conjures up the Burren, and Ireland itself, well enough for me.

All Photos Copyright Laura Read

Hanging with Headhunters in Nagaland - San Francisco Chronicle Magazine

San Francisco Chronicle Magazine

THE JEEP BELCHED to a stop in a courtyard flooded with noonday sun. Dominating the space was a thatch-roofed building adorned with bulls-head carvings and decorated with flowers for tomorrow’s purification festival. Our guide, Sanjay Thakur, disappeared down a walkway to check us in to our bungalows. We cracked our tired joints and stepped into the cooling breeze. Across a ravine, sod and metal huts cluttered the hillside. Just as I’d read in anthropology books back home, they stood cock-eyed to each other so evil spirits couldn't move easily among doors. Behind them loomed a three-story Baptist church.

Our American tour leader, Bob Phillips, a retired Sacramento State University professor who now runs a small, word-of-mouth travel company, Mekong Tours, had already jumped down the hillside into a nearby yard. "Laura, take a look at this. Have you ever watched a pig being butchered?" Bob grew up on an Oregon farm. For him, pig butchering is nostalgic.

I shuddered. "Never have, Bob." My stomach was already gurgling with an unfortunate mélange of coconut cookies I’d bought earlier at police checkpoint.

But Bob was insistent: "Grab your camera."

I slung my Nikon around my neck and scuffed down the worn path after him. A sudden blinding flash of sunlight off a metal roof briefly forced me keep feel my way on the irregular terrain by foot. After I blinked, I was looking at a chopped off head of a flame-singed pig displayed on a firewood pile.

We were visiting the Angami Tribe of Nagaland, in their village of Touphema deep in the folding mountains of northeast India. Nagaland is named for its hill tribes, the Nagas, or "fierce people”. It encompasses the last wrinkles of the eastern Himalayan foothills, north of the Bay of Bengal. It also divides the sultry plains of Assam to the west from the country of Myanmar, (formerly called Burma), to the east. The Nagas had stopped chopping off heads in 1963 but had warred violently with each other over issues of independence from India until a ceasefire in 1997. Because of the state's remote location and the notoriety of its people, it had been closed to foreigners until 2002.

I was here to observe and photograph the mid-February Angami Sekrenyi Festival, a fertility ceremony of dance and song related to the planting season and recalling the headhunting activities that once scored their animist beliefs. I had known I’d see feast-making as part of the event, but had imagined a sauté, not a slaughter.

As we approached the butchering site, the hacking sounds intensified until they seemed to split my own bones. A satellite dish the size of a Volkswagen Bug screened out the Baptist church. Next to it, on a cement slab, five men crouched around a mess of meat and guts. Their muscled arms, shiny with effort, arced through the air, driving hand-forged blades through sinew and bone. As I moved in close with my wide-angled lens, the zinc-like scent of blood filled my nostrils and lungs.

“What an ironic introduction,” I murmured.

Before the Nagas converted to Christianity, they believed heads contained a life-force to be gathered in raids and hoarded. Cherished like gold, cleaned skulls were stockpiled in the eaves of houses or in underground burial spots. They influenced many aspects of village life: a boy was not able to marry until he secured his first severed head; a man who boldly "took" many heads was able to wear prestigious clothing and ornaments; and head-related symbols ornamented village gates and public buildings.

But all of that changed after the 1870s when Baptist missionaries thrashed through the jungles into the Naga Hills and delivered their convictions, along with their medicine and education, to the tribes. Disenfranchised tribes throughout the hill regions of northern India were attracted to the Christian promise of equality. In Nagaland, 98 percent of the population ties their fate to the will a single Christian God.

The Nagas are using tourism as a way to boost their economy as well as preserve their culture, artifacts and rituals. The best way to see the state is by visiting its many villages scattered throughout the jungly hills. But overnight facilities in those are rare. Only two villages have developed western-style lodging big enough for the groups. The Touphema bungalows and dining hall resembled traditional buildings, built of thatch and cement by local Angamis, and decorated with typical symbols. Lodge managers were skilled in English and often shared village stories. The food is a mixture of local and central Indian cuisine, usually delicious, occasionally surprising.

That night in the dining room, sautéed pork rested before me in a bowl on the buffet. I spooned the richly seasoned chunks onto my plate next to piles of white rice, nan, and steamed chard, then nudged Bob's elbow. "They've stewed the pork with potatoes."

"That's not potatoes; it's fat."

I quickly shoveled the flabby white chunks back into the bowl.

One engaging manager I met was Khrienno Kense, who three months ago had married a Welsh man and made an unlikely move to Wales. She was now home to help with the festival. After dinner, Khrienno pulled me aside. "If you like, I will lend you one of my meklahs to wear tomorrow during the ceremony."

I said I would be honored to wear the traditional ankle-length wrap skirt, and arranged to pick it up tomorrow.

The next morning, after feast of eggs and fruit outdoors, I looked for Khrienno in the dining room. From the kitchen, rumbling laughter indicated lunch-prep was starting. The giggles were no surprise: The Angami people were considered some of the most warm and friendly in all of Nagaland. Soon Khrienno emerged from the kitchen door, her skin glowing cool as porcelain, and handed me a folded skirt. I was amazed to see it was not the traditional black color bordered in pencil-thin pink and green stripes, but a ripe hue of tangerine.

"It is my favorite skirt, woven on a back loom by a friend," she said. "The locals will appreciate seeing you wear this."

I grinned. "I certainly won't disappear in the crowd."

I couldn't get the ends to tuck firmly at the waist, so Khrienno showed me how to hitch a corner into the top fold and let the tightly-woven cloth fall smoothly to just above my hiking boots. Wrinkles are a sign of the novice wearer, Khrienno said. There were no pins or buttons, so I added extra security by cinching my hip-belt camera bag over the waist folds.

"Promise me you won't remove the camera bag without checking that the skirt will stay up," Khrienno said. We laughed together and I left, feeling wrapped in spun gold and trying hopelessly to conceal my skirt-bound waddle.

Nagas look different from the east Indians we Americans are used to seeing on TV or in travel literature. Their skin is lighter, cheekbones wider, foreheads broader. According to anthropologists, they are related, instead, to the Mongolians, and speak dialects of the Tibeto-Burmese language. I objected to one early recorder's assertion that the men were handsome, the women plain. The women were exceedingly handsome -- gorgeous even, their beauty amplified by broad, natural smiles.

The men's athletic beauty was enhanced by their Sekrenyi uniforms. When I strolled into the festival courtyard, where the dancing was to take place shortly, I spotted performers helping each other into outfits. A couple of men were practicing harmonies. Preparing my camera, I moved close to the group. The whisper of my shutter mingled with the baritones. They welcomed me with smiles. I hopped behind a log where they'd placed their arm bracelets and hair pins. A girl pointed toward my feet. Oh, horror! I'd brushed against a sticker bush and the base of my orange skirt was covered in thorns. I reached down to see if I could pull them off without ripping threads and found they peeled off easily. The dressers continued their work, but one of the men helped me to clean off the horns.

With an hour to kill, I wandered into a building overlooked a plunging canyon. A man crouched barefoot, measuring strands of cane against a 6-inch square he'd drawn on the cement floor with a pencil. He was apparently preparing to make a basket, one of the primary tools of the village. During the drive to Touphema, I'd seen plenty of them filled with wood or green stalks, balanced on women's backs by straps to the forehead.

The entrance to the oldest part of Touphema was marked by a wooden arch decorated with carvings of a warrior holding a blood-drenched severed head – a reminder lest I forget the original natures of my hosts. Roosters crowed, women hung out the wash, and, at a neighborhood faucet, a girl washed her hair. I found an overlook encircled with stone benches and sat down. I had read that this kind of platform was a meeting place for elders and leaders. The view stretched over rooftops into a blue, leafy canyon. At home, this view would be worth a million.

Three men and a toddler joined me, and conversation quickly turned serious.

"Are you Christian?"

"Yes, but not everyone from our country is Christian. We have many religions."

"Mostly Catholic?"

"We have many others, including Buddhism and Muslim."

"Muslim?" They seemed astounded.

"In our culture, we try to be tolerant. It is one of the best aspects of American life." They nodded, uncertainly. I open my arms wide. "We embrace -- we TRY to embrace all religions. But we are not all successful at this. Some people can't tolerate others who are different. But we are one big stew pot -- being stirred over the fire." I laugh and they join me heartily. I gesture toward the tourist bungalows, their thatch roofs just visible over the hill. "Why do you want tourists here?"

The man with the toddler lifted the boy onto his lap. "We learn about your ways of doing things."

"What do you want to learn?"

"You are advanced.” He seemed to search for words. “Your homes are not built close together like ours."

"But that doesn't mean we have a better life."

"Your houses are not like this?"

"Not usually. They are in grids with sidewalks and paved streets. People spend most time inside their houses and when they come out, they get in their cars and drive somewhere. They all have cars, generally. But, look. Please keep in mind that just because a society is advanced doesn't mean the people are happier. Maybe we can learn from you. We pass each other in our cars behind metal and glass; you pass each other on foot and wave hello. We talk over the phone, without seeing each other's faces. You sit here on these stone benches. We settle things in court. You settle things in your neighborhood meetings, face to face. We don't have much time to gather together."

Another man says: "We have many opportunities to meet together."

"What does that do for your community?"

"We know each other very well. We share our different ideas. We understand each other."

"Do you have less conflict because of it?"

They give half-hearted nods, and then I remember they have big conflicts -- disagreements that have sparked terrorism against each other for forty years, and before that, clashes relating to chopping off each other's heads.

Time was up. I thanked them deeply for the conversation.

Back at the festival courtyard, the dancing started with chanting and the entrance of 30 Angami dancers wearing heavy bamboo headdresses representing the sun. They danced homage to nature to low, throaty chanting. Next entered a troupe in stunning criss-crossed vests in red, black, and white replicating garb used in headhunting raids. A piercing howl launched their wild circular dance. Some wore horns, and all of them carried small baskets at their waists mimicking those used during headhunting raids to carry sharp sticks that were placed in the ground to thwart pursuers.

Afterward, as I wandered again into the village, a gush of rapid-fire English erupted behind me. "My name is Medo Rio-- would you like me to show you around?"

She had two friends with her, but she did all the talking – at high speed. "It is a very beautiful skirt you are wearing and won't you come to my house I would like you to meet my aunt she will give you some tea." We followed a jeep trail past a kiosk selling soda and batteries, past a pen containing three black mithun, the Naga's favorite water buffalo, and up a short hill. Medo never stopped talking. "I go to school in Kohima (the Nagaland capital) and when I am here in Touphema I stay with my aunt and uncle." As we entered the smoky darkness of her hut, I cinched my meklah under my camera belt, hoping to smooth out un-presentable wrinkles. The interior was illuminated only by the glowing hearth. Dark corners dissolved into nothingness.

Medo's aunt unfolded from a stool where she was cooking by the fire and shook my hand. Her meklah was the rich color of eggplant. A strand of cornelian beads hung against her violet shirt. She had pinned her black hair loosely in a bun.

I bowed. "I am honored to be in your home."

"Oooh, ooh, oooh." She said, grinning and bowing.

"It means yes, yes." Medo answered my querying look. "She doesn’t speak English. Her name is Vila Rio."

Vila bent over the hearth and blew the embers to life with a hollow stick of bamboo. Naga houses don't have roof holes for the fire. Smoke filters into clothing and drifts out the door. Soot piles up on all the things stored in the room, including baskets, wooden plates, and vegetables hung to dry near the roof. The flaring fire lit up shelves stacked with a dozen plates, cups and plastic containers. Clean, bulbous aluminum water jugs gleamed from wall hooks.

As Medo chatted, Vila heated water and made me some tea with sugar and milk. Soon my brain felt tingly with the caffeine. "I love the color of Vila's meklah," I said. Medo fetched a folded purple bundle from one of the dark corners.

“Vila wants you to have this meklah," Medo said. "It is almost the same color."

I leaned away in surprise. "Oh, no, no, no. I am honored, but I cannot possibly take such a fine gift." It was not good manners to refuse a gift, but this one was too much for me to accept. However, I also did not want to imply I did not like it. I was socially stuck. "I would like to pay something for it. There is too much work involved in that for you to give it to me." Later I realized a gift exchange is far more meaningful to the Angamis than an economic exchange, but in the moment, I felt embarrassed, and wanted to give them the first thing I could think of – money.

The light outside soon faded. "I will guide you back with a flashlight," Medo said.

She put a match into a shiny soup can, and a candle mounted in wax inside flared. The can hung sideways from a wire handle attached to two holes bored into the curved topside. The flickering light was just enough to guide us. In the moments before my eyes adjusted, I had to feel my way by foot, relying kinesthetically on the uneven sensations of the ground against my boot soles. Through doorways and windows, I glimpsed shapes of people seated around the hearth, their soft voices and "ooh, ooh, oohs" now seeming especially soothing to me in the darkness. After saying goodnight to Medo and closing my bungalow door, I could not bring myself to flip on the electric bedroom light. The shroud of darkness nurtured me somehow. I lay on my bed, my tangerine meklah now wrapped lightly around my legs like a heavy sheet. My mind recalled the aromas of the day. The zinc tang of chopped pig and the nutty smoke of Angami hearths mingled with the real sharpness of my own end-of-day sweat. I drifted to sleep to the hum of voices outside – people rehearsing for the next songs of purification and good fortune, maybe, or else preparing for the next slaughter.

All Photos Copyright Laura Read

Sleeping with Polar Bears - San Francisco Chronicle

San Francisco Chronicle Magazine

Sometime in the night our bunkhouse shuddered. Then something roared. I looked out the barred window, which separated the inky night into disjunctive frames. Earlier, eight bears had been milling around outside. Now I was just able to discern their milky forms moving about like Martha Graham dancers on a ghostly set.